[December 12, 2025]

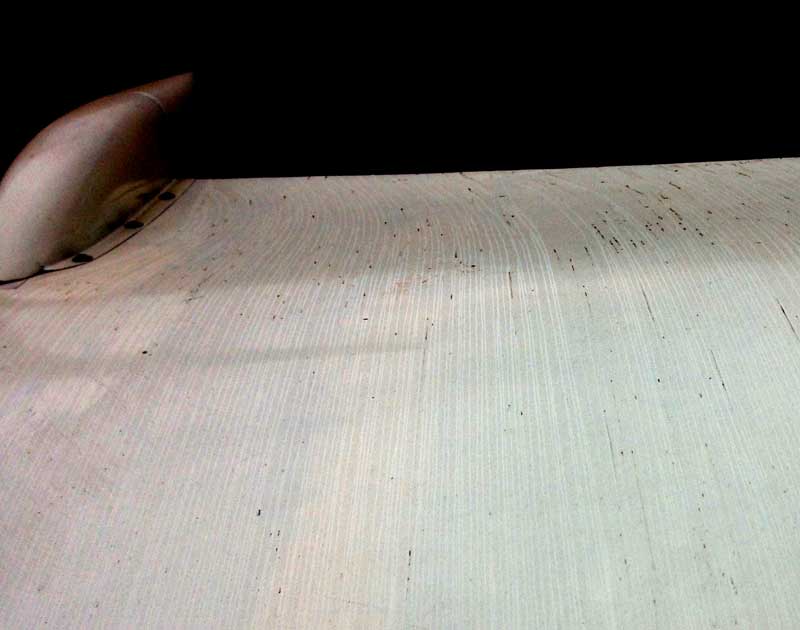

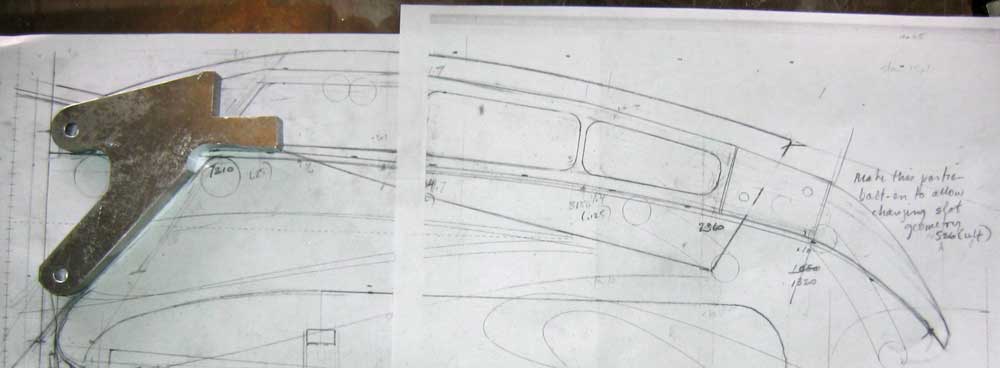

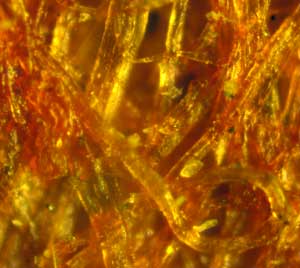

For the past ten years or so I've been aware of several very fine cracks in the upper surface of the horizontal stabilizer, where you had to go pretty far up a ladder just to see them. I marked the ends of the cracks with pencil and observed that they grew at a rate of at most 1/8 of an inch a year. It was very likely that these were filler cracks, since they were not in a particularly highly stressed area. I finally decided to make sure, and sanded away the area in question, down to the lamination. Embarrassingl, the filler was about 1/8 of an inch thick at that particular location. It's not that bad everywhere. The underlying skin was fine, so I just had to fill up the hole I had made, which was about 3 by 4 inches. This is done with a mixture of epoxy and plastic microballoons, which resemble flour but are much lighter, each microscopic particle being -- if not broken -- an empty bubble. You could fill a page, in a small font, with detailed instructions on how to fill a hole, from how to mix the epoxy-microballoon filler so that it is as dry as possible but not too dry, to how to wet the bottom and edges of the hole with a very thin smear of epoxy and press the filler into the edges so that tiny gaps don't appear around the perimeter when you sand the filler, and how to mound the filler slightly above the surface contour and then sand it down after it cures. The reason you do it that way is that, as with Bondo, it's desirable to do the filling in a single pass and not to keep filling low spots with additional layers. Multiple rounds of filler risk producing regions of slightly different hardness that sand slightly differently. At any rate, I managed to fill and smooth the wound pretty satisfactorily. I then found a can of "ivory" spray paint whose plastic cap, which is supposed to show the color of the paint, exactly matched the paint on the airplane. Unfortunately, it did not exactly match the paint in the can, but no matter, since 1) areas painted with the actual original paint, but years later, are even less similar and 2) nobody brings a ladder to look at my airplane anyway.[October 13, 2025]

I was mid-sentence in the process of replying to an email from Dan Fritz, who had made some suggestions regarding the sump drain question, when it dawned on me that if I was going to have to open the airbrake to get access to the sump drains, the drain valves didn't have to be crowded into the tight gap between the wing and the edge of the airbrake; they could make use of the ample space above the brake itself. Weird how the mind works, or rather doesn't.[October 9, 2025]

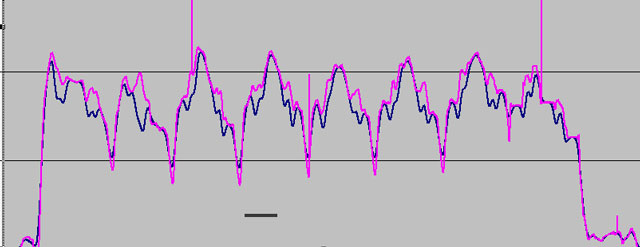

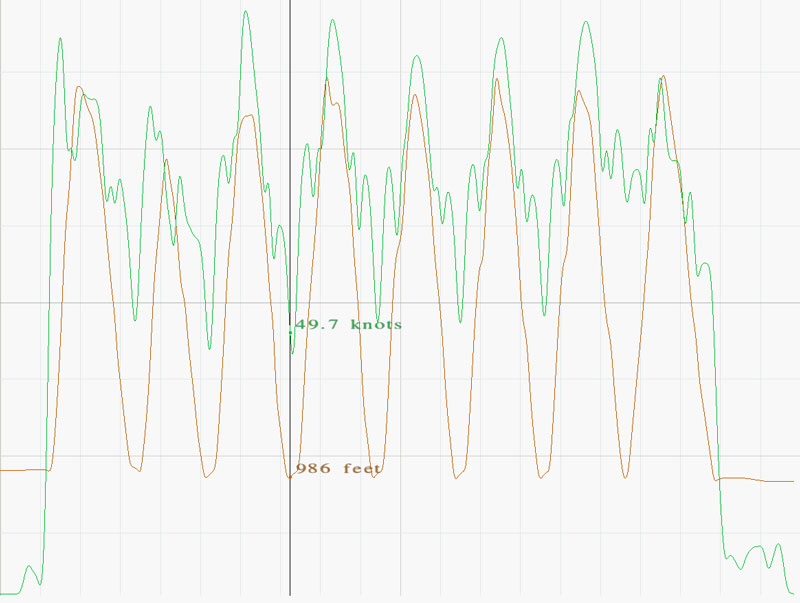

I recorded a couple of speed points today. The air was extremely smooth, and there seemed to be no vertical movement in the air mass; but one can't be sure. I was at 10,500 feet, density altitude 12,000. At 23/2300, lean of peak, I saw 174 knots true (145 kias) at 8.3-8.4 gph, or about 57% power. My generally reliable computer simulation says that I should have been using 9.8 gph at that speed. Seldom have I seen it so far off. I then set the power at 21.5/1900, and got 152 ktas (126 kias) at 7.1 gph (45%), which is exactly in line with the simulation. I can't account for the divergence; the simulation is normally in good agreement with experience. Incidentally, the engine is pleasantly smooth and quiet at 1,900 rpm; I would use that setting more often, but it coincides with some blade resonances that I should probably avoid.

[October 2, 2025]

[September 24, 2025]

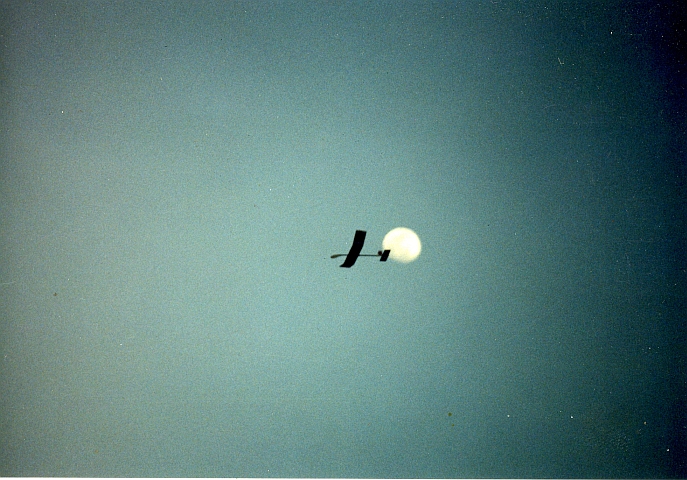

I got to the airport for the first time since returning from the east coast a week ago. It was unexpectedly moving to see the plane, which I had washed just before leaving, gleaming marble-white in the hangar's filtered light. For a couple of minutes I just stood and gazed at it, like a person lingering over a just-rediscovered photo of an old love. I recall a lovely sentence of George Eliot, from Adam Bede: "It was that moment in summer when the sound of the scythe being whetted makes us cast more lingering looks at the flower-sprinkled tresses of the meadows." In this case, the scythe is being whetted for me. Flying has decided to run my two columns alternately rather both in each issue. This deprives me of about a third of my already exiguous income, and makes my ownership of an airplane even less defensible than it was before.[August 19, 2025]

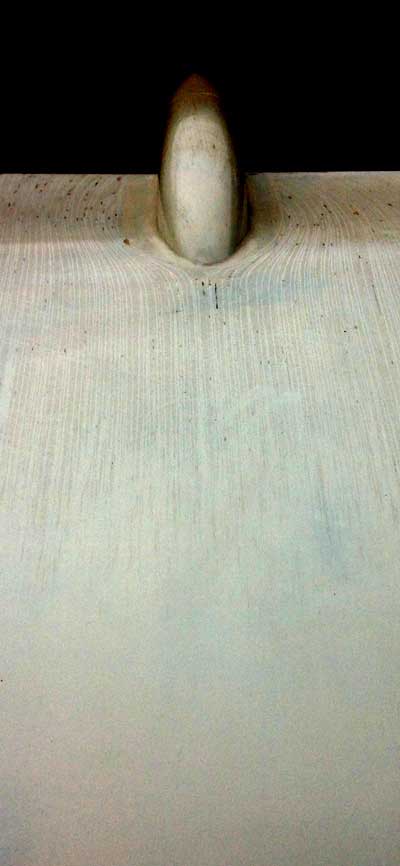

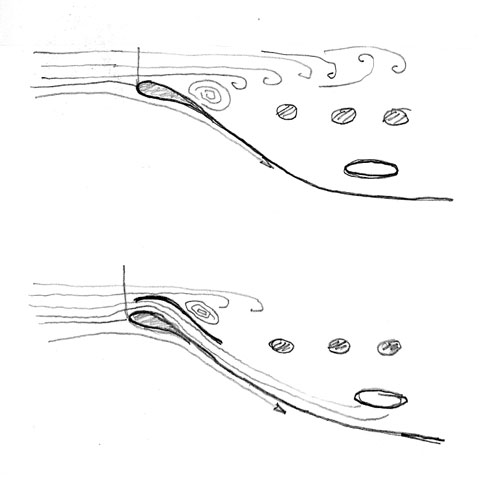

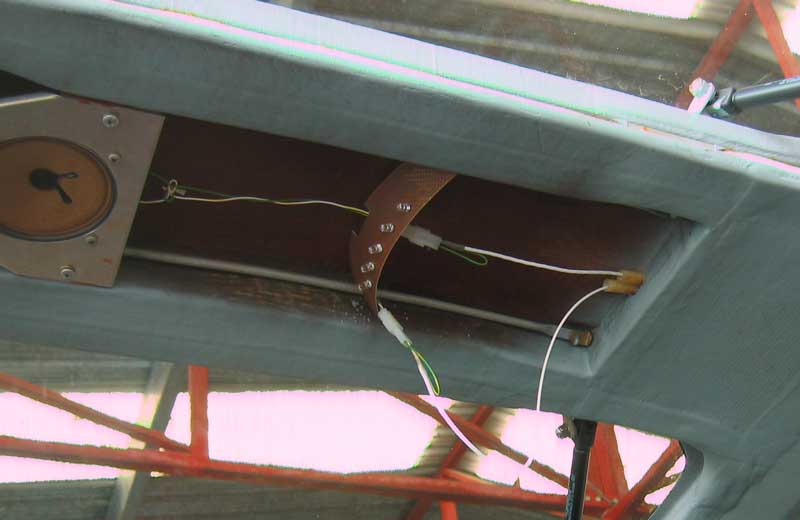

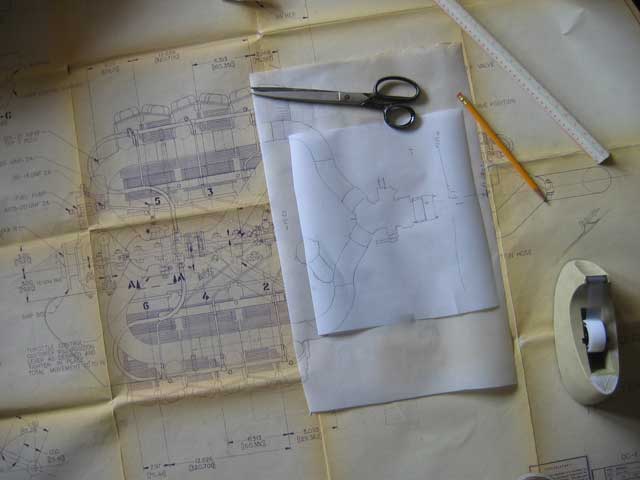

Back in January, 2007 I installed a fairing around the exhaust pipe. Its intended efect was to preserve a more or less coherent boundary layer between the exhaust stream and the fuselage, thereby preventing staining and leakage of exhaust into the cabin. For some reason, I failed to take the precaution of using my analysis software to determine the angle of flow in the vicinity of the exhaust. As exhaust stain built up on the underside of the fuselage, it was apparent that the fairing was misaligned. Now, after ignoring this annoying imperfection for 18 years, I finally got around to re-orienting the fairing, which turns out to need to be at a (surprisingly large) 10-degree angle to the airplane centerline (trailing edge outward). Until I've flown a few times, it won't be clear whether this modificatoin did any good.

[August 13, 2025]

The other day I was flying and noted down the fuel flow, density altitude and indicated airspeed. I later checked the numbers against my computer simulation and was glad to see that they matched precisely. That the simulation is a good predictor of the performance of the airplane would have no particular significance, unless one were planning a flight over a very long distance. I am not planning such a flight, except in imagination; but suppose, for example, I wanted to fly to Hawaii. Then the ability to simulate the performance of the airplane at various weights and power settings would be quite helpful. The shortest distance is Oakland to Hilo, around 2,330 statute miles; Los Angeles to Honolulu is 2,555. With 140 gallons of fuel usable in level flight, and able to cruise at 180 mph at 9 gph even at gross weight -- fuel flow drops as weight diminishes -- the plane can obviously make the Oakland-Hilo trip with good reserves. It could even make it in under 12 hours, but the cushion gets a bit scanty, with 19 spare gallons for taxi, climb and reserve. What is noteworthy is that it's not necessary to fly anywhere near the airplane's best-range speed, which would not only make for an agonizingly long and slow trip, but would in fact use more fuel than a higher speed. The reason is that the specific fuel consumption rises considerably at very low power settings, and the best L/D speed, 103 imph at 2,100 pounds and 119 at 2,800, occurs at between 35 and 39 percent power. What you're really interested in, if you want to go the longest possible distance, is not the best L/D speed but the speed for best specific range, that is, the most miles per gallon. That occurs, for example, at between 138 and 155 mph TAS at 12,500 feet. Note that L/D speed is an IAS, invariant with altitude, whereas specific range speed is a TAS and therefore increases with altitude. So for the quickest trip you would fly at the highest altitude you could; at 20,000 feet you could cruise at 200 mph and arrive with more than 30 gallons in reserve, but an empty oxygen tank.[July 5, 2025]

I modified the lidar gear warning software to make the beep rate of the alarm signal inversely proportional to height; this is supposed to convey a sense of urgency as I descend gear-up toward the runway wondering what that beeping noise I'm hearing is all about.[October 16, 2024]

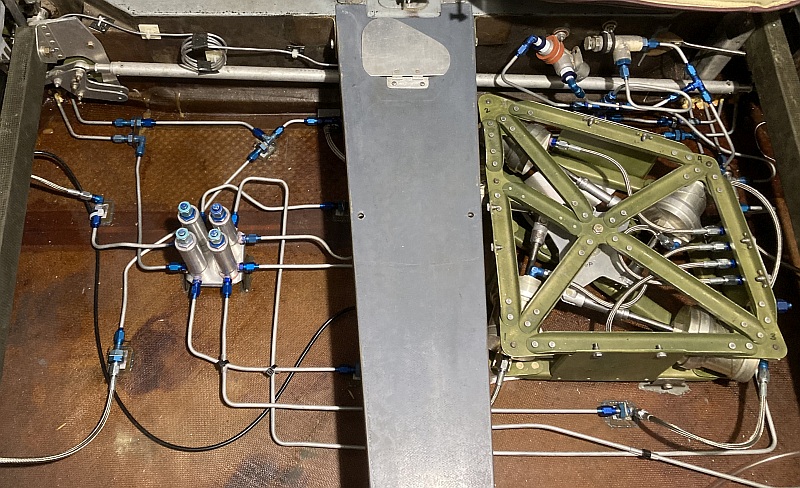

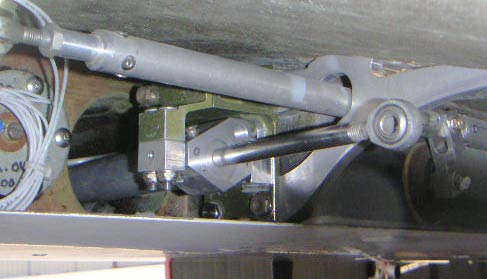

My casual prediction that at the rate I was going the last couple of hose replacements should take me through the fall proved to be correct. I finally finished that project today. The final step was the most complicated, and involved removing the inboard flap actuator cylinders and replacing the hydraulic lines coming from the far aft ends, which were simply lengths of nylon tubing secured to the cylinder with tie wraps, with hard tubing terminating in an AN bulkhead fitting. The bulkhead fitting is secured to a flange that protrudes from the side of the cylinder at a right angle, and is bonded to it with silicone caulk to allow the cylinder to expand under pressure. Now the tie wraps pass under the hydraulic tubing, to keep it from rubbing against the cylinders. Whether this whole operation was worthwhile is questionable, but at least it looks better than it used to, and will certainly not be subject to connections popping loose under intense solar heating of the hydraulic fluid, as happened twice with the nylon plumbing.

[June 20, 2024]

After being away most of the month of May and half of June, I finally finished the installation of the lidar gear warning system and flew the plane for the first time in 3 months. It started instantly and seemed none the worse for the long period of idleness. I found that I had by now forgotten which color wire I needed to disconnect to override the gear position signal and test the lidar portion of the system, but that can wait. Ironically, returning to Whiteman, when I was a mile or so out, I ran the landing checklist and found that I had failed to put the gear down. I attribute that oversight to my approaching fast straight in, so as not to inconvenience the airplane turning base behind me. I slowed from 130 to 100 knots rapidly with the airbrake, then put down half flaps. This was a deviation from my normal practice, which is to put the gear down before the flaps. Perhaps I unconsciously consider the flaps a confirmation that the gear is already down. If so, I had better make it my unvarying practice to do gear first, then flaps.[April 13, 2024]

Yesterday I began installing the gear warning system. The first step was to track down the wires going to the up and down lights on the panel, and I discovered that my recollection of the system, which I installed several years ago, was all wrong. I had mixed up the microswitch that enables the landing lights to operate (they are on a gear leg, and so don't light when the gear is retracted), with the switches -- it turns out there are two -- that trigger the gear position lights. So I actually have a "gear down" signal available, not just a "gear up" signal, and the ambiguity of a null "gear up" signal, which could mean gear down or gear in transit, is removed.[April 11, 2024]

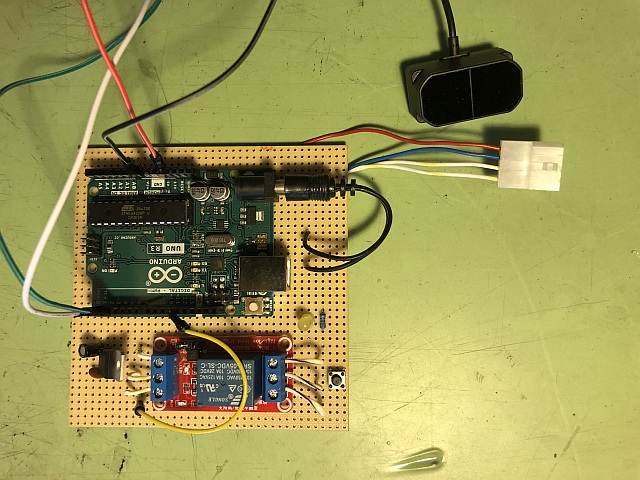

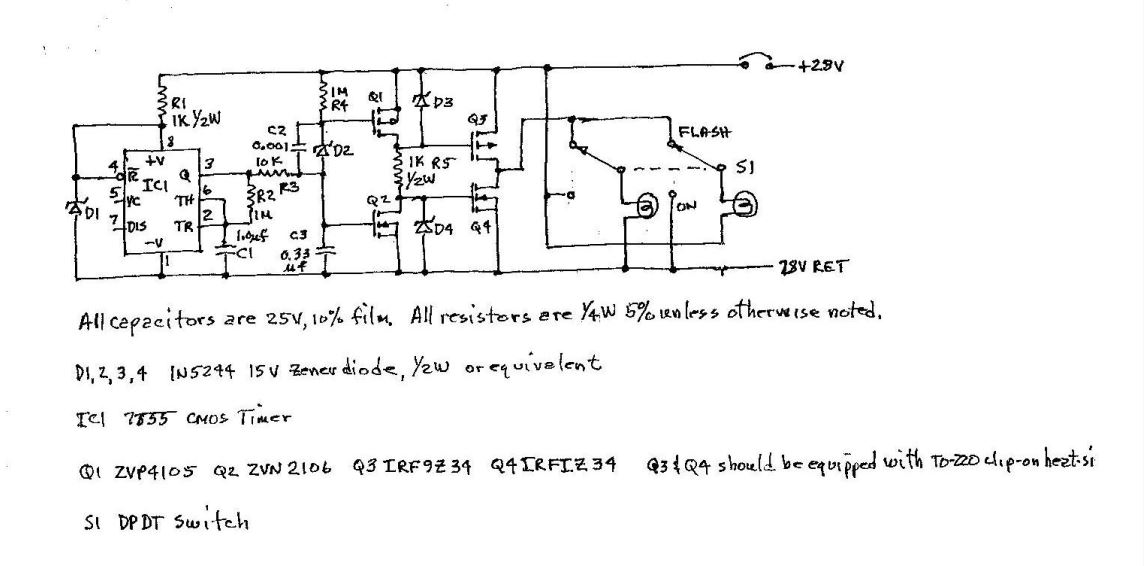

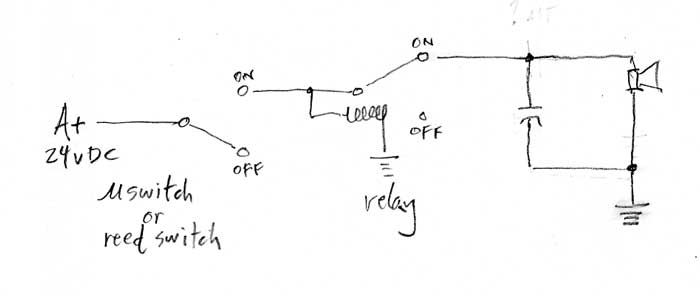

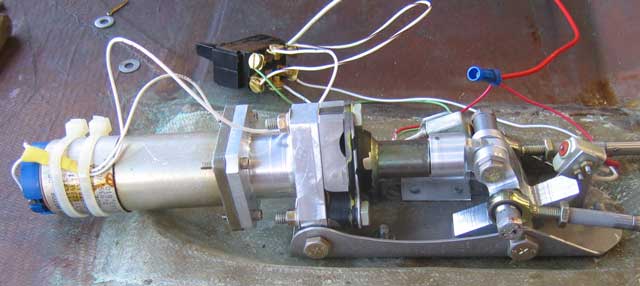

I finally assembled the lidar rangefinder gear warning system, but have not yet installed it. It consists of a lidar rangefinder, an Arduino computer and a relay. When the rangefinder tells the computer that the distance to something below the airplane is less than 30 feet, the computer energizes the relay. The relay in turn completes a circuit that gets power from the "gear is up" branch of the gear position microswitch. If the gear is not up, that circuit is not energized and so nothing happens. If the gear is up, the circuit is hot and an alarm sounds. There is an LED that lights whenever the rangefinder says the plane is below 30 feet agl, whether or not the gear is down, and a press-to-test button to check, from time to time, whether the beeper is working.

[February 13, 2024]

I have replaced all but two of the nylon lines with proper aluminum and a small fortune in AN fittings, and am now having a hard time bleeding the system. I realize now that certain components could have been better designed to avoid trapping bubbles; unfortunately it is unlikely that I will ever get to apply that knowledge. In the meanwhile I have also begun working on a landing gear warning system using a lidar sensor to trigger an alarm when the airplane is less than, say, 30 feet from the surface and the landing gear is not down. I have never done much with electronics before, but with the help of Peter Lert and YouTube, anything is possible.[December 15, 2023]

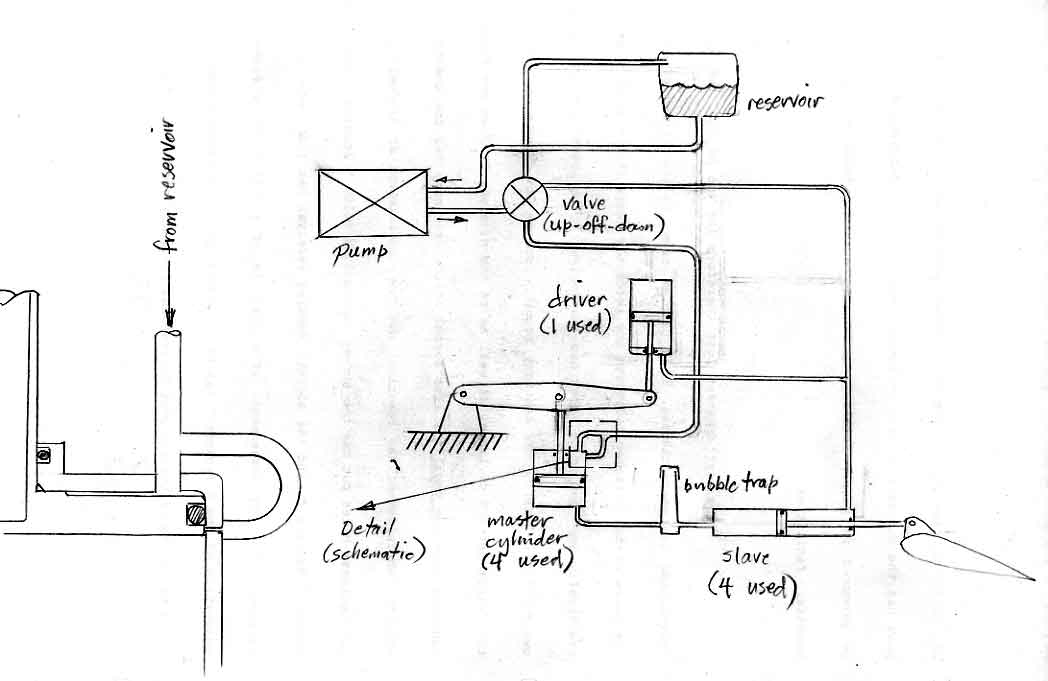

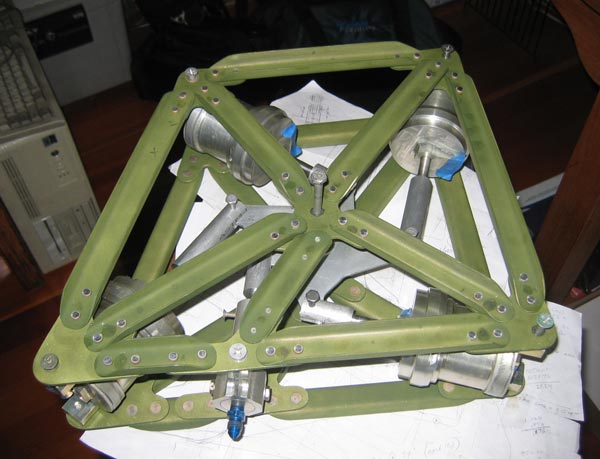

Having rehearsed the procedure in my mind a great many times, I set out to replace just one of the nylon hoses in the flap synchronizer with an armored hose with AN flare fittings, etc. It turned out to go more smoothly than I had expected, and in a couple of hours I did all four of the main feed/vent connections. Luckily my visualizations had forewarned me to partly lower the flap before making the change; that way the air that got into the system would be flushed back to the reservoir when the flap was retracted. I will not be able to attempt the next step until after Christmas, the time between now and then being consecrated to making cookies for our annual Christmas party which, after two years of Covid and one of Nancy's broken hip, is resuming its otherwise uninterruped 35-year run. The next step will be to connect the master cylinder outlets to the bubble catchers, four little towers that are supposed to collect any air that finds its way into the lines between the master and slave cylinders. I anticipate that stage being simpler than the first, which required partly dismantling the synchronizer frame; all of the fittings for the second phase are accessible from outside the frame.

[September 28, 2023]

After some floundering around I learned that you can buy the plastic breakable link for a Rapco vacuum pump. It came today. The chief mechanic at Able Air told me that once one of these things has failed you might as well get a new pump, because it's friction in the pump that caused it to fail. However, I can't discern any friction in the pump, so I'm going to give it a try. The worst that can happen is that the pump fails again, which won't matter, since I no longer fly IFR. In the course of removing the pump I discovered that a steel bracket, whose intended purpose was to stabilize the throttle body, had fatigued and broken. The break could not be seen, I have no idea when it failed; I installed it in 2014.[September 6, 2023]

A while ago I received a card inviting me to join the octogenarian pilots' association. I have not yet acted upon it; the reality takes time to sink in.[March 5, 2023]

The trim system is pleasantly smooth now, demonstrating that lubricants are not all they're cracked up to be. I checked compressions; three were 80/80, none lower than 77/80, surprisingly good for an engine that qualifies, on time flown alone, as run out. Spectroscopic oil analysis after changing the oil found no ill omens. The radios -- Collins MicroLine dating from the 1970s -- are getting a bit weak; I may need to stop using earplugs under my headset. The airplane's main problem now is hydraulic leaks. I keep toying with the possibiity of replacing all of the nylon lines I now use with a combination of hard aluminum lines and a bunch of short Aeroquip hoses to accommodate cylinder movement. As I mentioned last June, it's a project that would cost quite a bit of money and might yield little or no improvement, since the leaks may be principally in the cylinder seals.

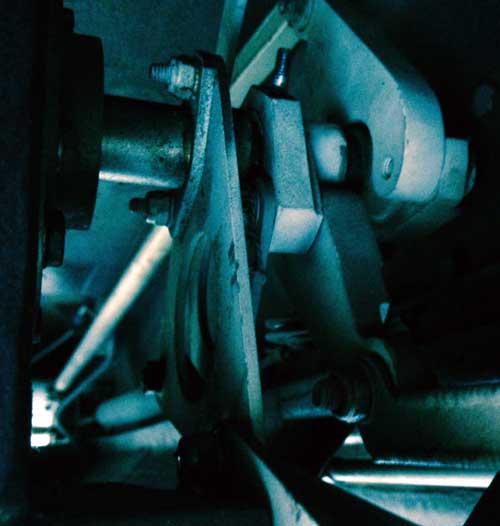

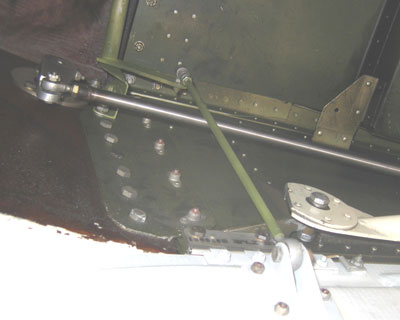

The

reason for

the peculiar position of my right arm is that the gear is in transit.

The gear handle must be held in the "up" (or "down") position

while the gear is cycling; it is returned to the center detent once the

gear is up or down. The flaps work the same way. Both flap and gear

handles are connected by cables to closed-center hydraulic

valves, and directly actuate microswitches to energize the

hydraulic

pump.

[January 17, 2023]

Having gotten the trim system back into shape, I noticed that there seemed to be some friction in the elevator circuit, so I pulled out the hinge pins and cleaned and dry-lubed them, one with Molykote and the other, when the Molykote spray can clogged, with some stuff from Home Depot called Blaster. The elevator is still not exactly frictionless, but at least the friction is more or less constant throughout its travel, not variable as it was before.[January 3, 2023]

Nancy being at last sufficiently mobile that I can leave her alone in the house, I was at the airport yesterday and today trying to track down the cause of the extreme stiffness, indeed virtual inoperability, of the pitch trim. After exonerating the trim jackscrew, whch I originally assumed was the culprit, I finally homed in on the sprocket that converts the linear movement of the trim cables, via a length of bicycle chain, to rotary motion in the jackscrew. Apparently, long ago, in an effort to gild the lily (or, as the bard actually put it, to gild refinèd gold and paint the lily), I greased the bushing that supports the sprocket. In the course of (much) time the grease dried out, and now the sprocket would barely turn. I was kicking myself for the inaccessibility of the assembly, and had already taken a bunch of stuff apart (including removing the rudder), when I realized that all I really needed to do was take out the elevator bellcrank and I could remove the sprocket and its supporting bushing easily. I cleaned up the bushing, put the assembly back together dry -- aluminum is a perfectly good low-speed bearing surface for a steel shaft, even without lubricant -- and re-installed it. Now I just have to undo all the unnecessary disassembly of the surrounding structure. Actually, it has not been a complete waste of time; I was able to inspect a lot of hidden pieces and confirm that everything is holding up. I was impressed by the ingenuity with which I (not I who am writing, but an I of many years ago, practically a stranger to me now) had modified and cobbled together various pieces of a much longer linear actuator to make the current trim system. It really isn't bad at all.[December 7, 2022]

I flew today for the first time since September 22. My long absence from the upper air was not voluntary. Nancy and I spent the month of October in Ojai, with only occasion brief returns to Los Angeles, helping our son manage his two kids while their mother was doing a 30-day yoga program in Bali. No sooner did we get back than Nancy fell and broke her hip. She was in the hospital for three weeks, two of them in rehab getting physical therapy. I was with her most of the time. Now we're back home at last, and a day finally arrived when our daughter Lily, who came out here from New York between jobs to help, could hang out with Nancy while I went flying. Too much information, I admit. Anyway, the plane still flies, although now that colder weather (actually, standard atmosphere) is here the grease that I foolishly put on the pitch trim jackscrew has stiffened up and made the trim practically inoperable. I have to take the assembly apart, clean the screw and nut, and lubricate them either with dry graphite or not at all.[September 22, 2022]

I did a speed check today at 10,500 ft. The density altitude was 13,000. Speed seems to be a little off the expected numbers; at 25/2300, 25 LOP with a fuel burn of 9.9 gph, I got a true airspeed of 184 knots, versus an expected 189; or, to put it differently, versus an expected 9.5 gph. My engine is around TBO, and while I believe even an old engine will develop rated power, I'm not sure it will develop rated sfc. Since I use a curve-fitted sfc model to determine power for purposes of performance calculation, if the actual sfc is higher than I am assuming then the engine is developing less power at a given fuel flow, and so speed would be below the predicted value.[August 2, 2022]

Sure enough, the problem with the landing/taxi light was a broken ground wire, which I found and fixed. I seem to have suffered an unusual number (two) of broken ground wires lately; the reason is probably related to the fact that a composite airplane does not have the convenience of airframe ground, and so uses a great many more ground conductors than a metal airframe would. In many instances I used shielded conductors with the shield as the ground return, but not in the case of the landing light.[August 1, 2022]

Today I revised the wiring connections for the switch panel, and in so doing I found the broken ground wire that was the reason for the anticollision lights not working. Now they work, and, collaterally, that particular patch of wiring is a little better organized than it was before. Tomorrow I will tackle the problem of the inoperative landing lights. It will probably turn out to be something similar. I always imagine electrical gremlins to be more devious and subtle than they really are.[July 29, 2022]

The persistent refusal of the so-called strobes (they are actually halogen lamps) to work continues to baffle me. I have tried to troubleshoot the problem armed with a digital multimeter and almost zero understanding of electricity, and gotten about as far as I deserve to. The wiring behind the panel is not so well organized and labeled as one would wish, to put it mildly. Generally, my wiring resembles that of a Delhi slum. I decided to do some housekeeping there on the assumption that I would stumble on a solution to the strobe problem in the process. Actually, what I have stumbled on so far is that the landing/taxi light is not working either. They have nothing in common other than a 15-pin Molex connector that I've decided is too crowded with wires, so I'm dividing its occupants between two smaller connectors, one for the nav/panel/landing lights and another for the strobes. The flasher circuit was designed by the late Paul Lipps, who also made me the little board that operates it. It incorporates some ingenuity to increase bulb life; in the words of a caption, "This unusual dual-bulb flasher eliminates high inrush currents by using one bulb's heated filament to limit the starting current for the other bulb." This refinement may be superfluous, since the small halogen bulbs I use are practically given away and I don't fly at night anyway.

[May 5, 2022]

Cinco de Mayo! And with it --- well, nothing, actually. Yesterday I flew around for an hour, going, as usual, nowhere. I noticed that the left main strut was a little low, which is surprising, since with warmed weather you'd think it would get a little higher. It's been years since I've added air to the struts; they hold air well. I dipsticked the fuel, and found that it perfectly matched the totalizer. This seems always to be the case, although I never set the totalizer by the dipstick value, only by the gallons added. The totalizer is an old Alcor that Mike Melvill gave me; the company, whose employees are all younger than the totalizer, now denies any knowledge of its existence. The so-called strobes still aren't working, I don't know why, and the Lowrance GPS is increasingly demented, but who isn't?After I finished that chore, I was lying under the plane trying to figure out where a hydraulic fluid drip was coming from and to decide whether it was even serious enough to bother tracking down. I suspect the airbrake actuator; its O-rings are about 20 years old. My main gear actuator is also a possible culprit. It came from an Aztec, I think, and I can't remember now whether I overhauled it before I installed it, which was maybe 25 years ago. If either of those is the source of the leak, I won't be surprised. Maybe both are. But I couldn't summon the energy to pull either actuator, so I just lay there looking up into the well where all the hydraulics are and thinking, "God, I did this?"

At some point recently my "strobes" -- they're really blinking halogen lights -- stopped working. I have tried to track the A+ and ground wires through the maze behind the panel to find the problem; so far no luck. On a more cheerful note, I got a comm radio (Collins MicroLine VHF-251) on eBay for $150 to replace the one that quit. It works reasonably well -- well enough for a backup.

[January 3, 2022]

My anxiety about the apparent inaccessibility of my oil screens turned out to be a case of hypochondria by proxy. Though I could not recall having inspected the oil screens -- there are two, a suction screen and a pressure screen -- I probably had done it at some point in the past 19 years. And, although it took a little fancy wiggling to extricate them, it was not necessary to make a hole in the engine mount to do so. And both screens were perfectly clean; washing them with acetone liberated exactly nothing. So my concern about oil starvation due to a clogged screen turns out to have been unnecessary. The time and trouble were not wasted, however, because knowing that the screens are clean is roughly equal in importance to their actually being clean. Incidentally, it's not surprising that the "pressure screen", through which oil returns to the sump, is clean, since oil passes through the oil filter before reaching it. As for the "suction screen", it is very coarse and is apparently intended to prevent large fragments of a disintegrating engine, or perhaps nuts or bits of safety wire inadvertently abandoned by a careless overhauler, from getting to the oil pump.[November 23, 2021]

Nancy and I and three other couples went to Hawaii for a couple of weeks. We spent three days at Hilo and then went to Hanalei on Kauai for the duration. It was fun. I came back with a pair of flipflops called "Locals" which to my surprise were immediately recognized by a passerby as a sign of my having recently been to Hawaii. You never know what people are looking at. When I flew after coming back I found that the fuel totalizer had apparently regained its long term memory and was again retaining the fuel remaining from flight to flight. My next job is going to be to cut an access hole into the engine-mount-cum-nosewheel-box so that I can get the oil screen out of the crankcase. It has been blocked in there lo these 20 years, but I just read an NTSB report about somebody's engine quitting and the oil screen being found half full of schmutz. Apparently it hadn't been inspected in 11 years. I am a little skeptical of the attribution of a sudden engine failure to a partial obstruction that must have accumulated very gradually, and I put faith in my oil filter, but as a matter of principle I guess the oil screen should be accessible.[October 7, 2021]

I finally finished installing the new tailBeacon. The first couple of PAPRs I got reported NIC and NACp discrepancies, but I think those may have been due to the mountainous route I flew from WHP to Santa Paula and back, so I am not panicking yet. There has, however, been a series of other unfortunate, if minor, annoyances. One cushion of my David Clarks began oozing silicone gel down my neck. (This is the second time this has happened, by the way. The first time I had just landed at Kendallville, Indiana when I dicovered the reason my neck felt so greasy. By chance, a Blanik landed soon after me, and its pilot turned out to be a manufacturer of silicone gel. I remarked that I hoped it did not have flesh-eating properties. "If it's okay for breasts, it's okay for necks," was his reply. Actually, breast implants have had a checkered history, but my neck seems okay so far.) Then my fuel totalizer stopped remembering the fuel remaining from one flight to the next. Most likely the problem is failure of an internal battery, but it could be something more dire: the eventual decay of semiconductors, which has rendered both of my Lowrance GPSs mere shadows of their former selves. Finally, the new direction of Flying threatens to make of me that rarest of rarae aves: an airplane owner with an income below the poverty line.[August 25, 2021]

After many delays the tailBeacon went to uAvionix for repair. Nancy and I are going to the East Coast for two or three weeks, so it will not be back on the airplane until mid-September. In the meantime I have accomplished nothing besides adding the stout ground wire -- 14 gauge, as it turned out -- linking the aluminum frame on the aftmost bulkhead to the nearest airframe ground, which is the instrument panel. I was about to cut a hole in the afterbody of the engine/intercooler airscoop for a dedicated flush air inlet for the pilot, but I began to wonder whether putting a NACA scoop on a narrow raised surface was such a good idea. I could put it above the afterbody, but I have been discouraged from doing that by concern that hot air from the various top-surface cowling outlets might get to it. I doubt that could actually happen, but by the time I make up my mind the weather will have cooled off and an extra airscoop will seem less desirable, so the whole project may drag on until next summer. In the meantime Flying Magazine has been sold yet again, with what consequences for me remains to be seen. Flying has been the reason I have been able to spend my life messing about with airplanes; I hope that doesn't change.[July 30, 2021]

At the beginning of July, I got a stern letter from the FAA telling me that my ADS-B performance was not up to snuff, and giving me 45 days to shape up. My NIC was out of tolerance. Don't ask. I got in touch with uAvionix support, and they said it was probably a matter of the ground resistance, which should be less than half an ohm. This was the first I knew of that requirement; I don't know whether I overlooked it when I first installed the tailBeacon or they did not think it worth mentioning. Low ground resistance is easy to accomplish in an airframe made of metal, but takes more attention in a composite airplane, especially when the nearest ground plane -- the instrument panel frame -- is 18 feet away. I had supplied a rather fine ground wire, 20 or 22 gauge, and its resistance was around 1.5 ohms. Apparently it was right on the edge of okay, because I've been flying for more than a year and a half with the tailBeacon and this is the first time the FAA has complained.[June 24, 2021]

Nancy finally finished proofreading Aloft yesterday. She found a bunch of typos and scanning errors, so my rashly publishing the ebook on June 1 was obviously a mistake. If anyone rashly bought it (Rule 1 of software: never buy v.1.0) and would like a copy with the errors fixed, let me know and I will PayPal or otherwise send the $8 so that you don't need to pay for it twice. The paperback version should be available on Amazon in a couple of days. Incidentally, some guy who writes fantasy fiction has chosen to do so under my name, heaven knows why. I am not the author of The Magic Dead (Changeling Saga #3).[June 3, 2021]

A couple of days ago I had a bad runup: big drop, rough, and didn't get any better after I ran up to high power and leaned. The problem occurred when I turned off the mag switch labeled 'L". Did 'L' mean I was checking the left mag, or turning off the left mag to check the right? I wired the system 20 years ago, and it's been so long since I've had a bad mag drop that I'd forgotten what I was thinking back around 2000. I also wasn't sure how the mags related to the plugs -- the leads are a confusing jumble of identical wires -- but I suspected that the right mag assocated with the upper right and lower left plugs. Just to be sure, I asked an A&P, who said there was no hard and fast rule, and that he had even seen systems in which the right mag fed the right cylinders and the left the left -- an arrangement that seems to violate common sense, as he readily agreed. Eventually, on the advice of a different A&P, I ran up to 2,000 rpm, leaned to bring up EGT indications, and checked each cylinder. Turning off one spark plug slows the burn within the cylinder, so that the exhaust gases are hotter when they leave it. When both plugs are healthy, the EGT will rise during the mag check. The effect was not subtle. The EGT on #1 was much higher than the others' with both mags on, and when I switched off the left mag -- that's what 'L' means, as I found by checking the P leads with a multimeter -- it dropped to the peg. No ignition whatever on #1 from the right mag. I replaced that spark plug and the engine ran up fine. The faulty plug looked okay; there was no external evidence of failure.[June 1, 2021]

In a second venture into self-publishing, I have assembled 50 or so articles from my Technicalities column into a book called Aloft, which is currently available from Amazon (mea culpa!) as a ebook and will emerge in paperback form just as soon as Nancy finishes finding typos in the manuscript. It looks like this:

[April 2, 2021]

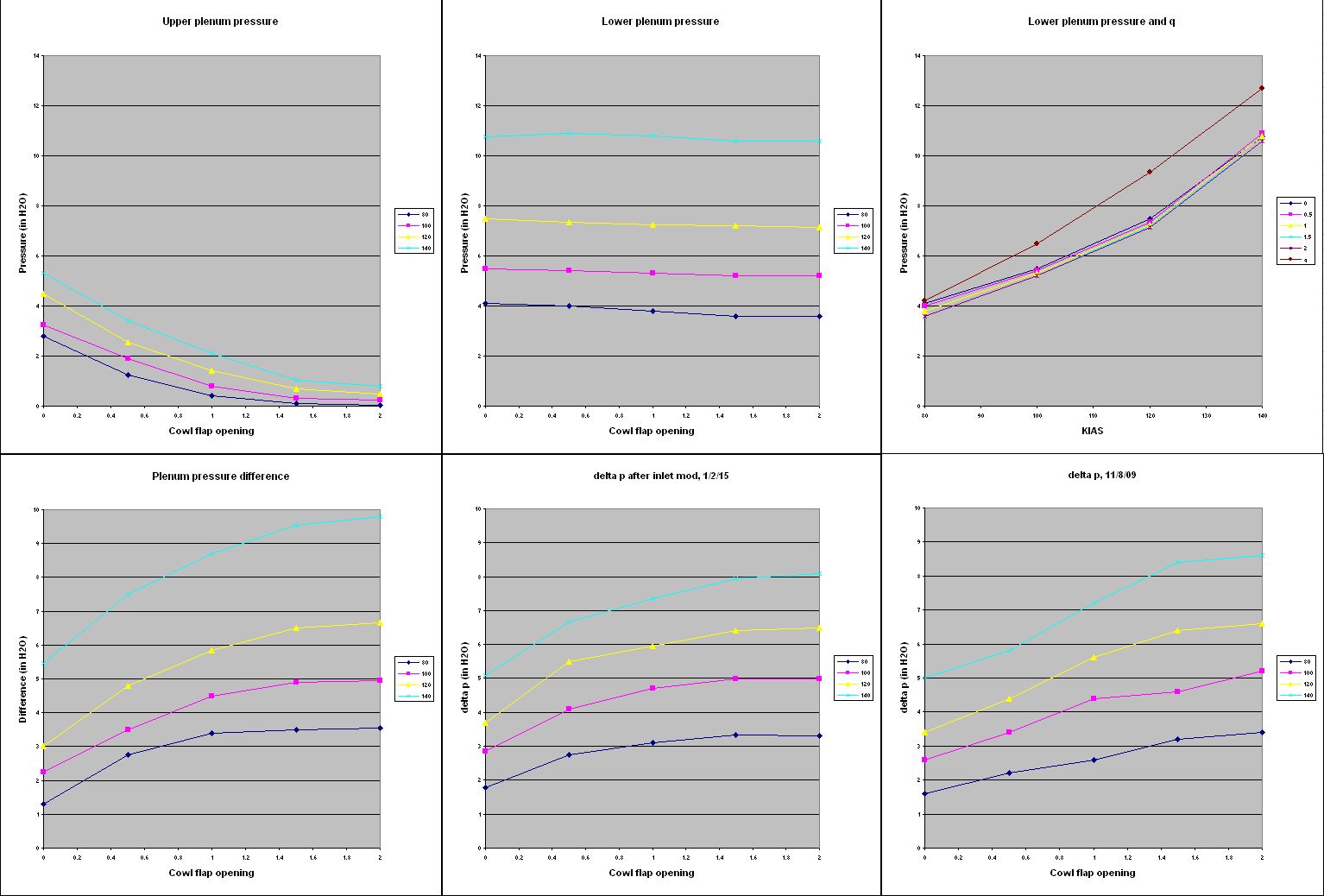

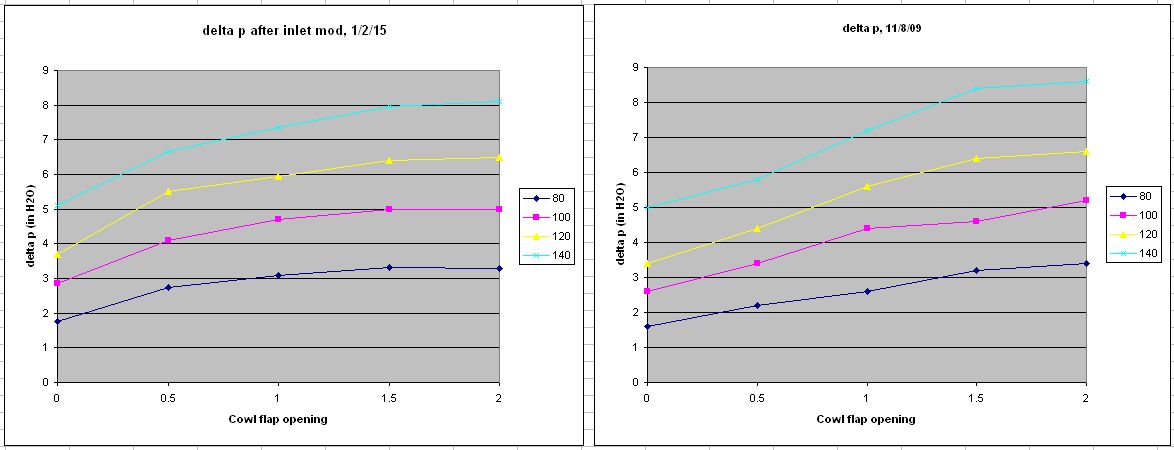

Yesterday the temperature hit 88, so, while it's still not exactly midsummer in the Rub al Khali, I did a quick oil temperature check using the digital system. The highest I saw was 193 F during a high power climb; cruising, it settled at 177. That is exactly the Vernatherm setting, so I guess the system has been working as expected all along, and my years of intermittent concern over high oil temperature readings were due to nothing more grave than a faulty panel instrument. The temperature did seem to be slightly affected by the cowl flap setting, so I will do some further tests to compare the current arrangement, where the oil cooler air vents into the upper plenum along with the cylinder cooling air, with the alternative, in which the oil cooler air shares a vent with the turbocharger intercooler air and is unaffected by the cowl flaps.[March 17, 2021]

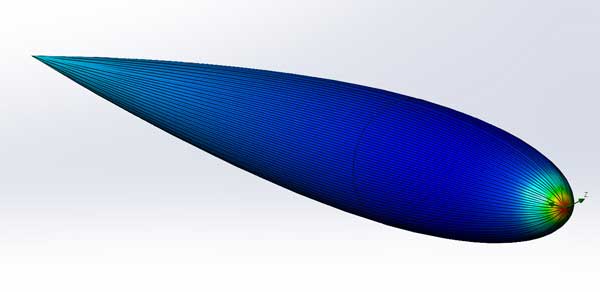

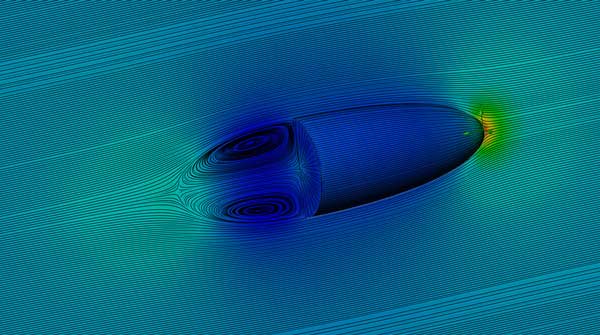

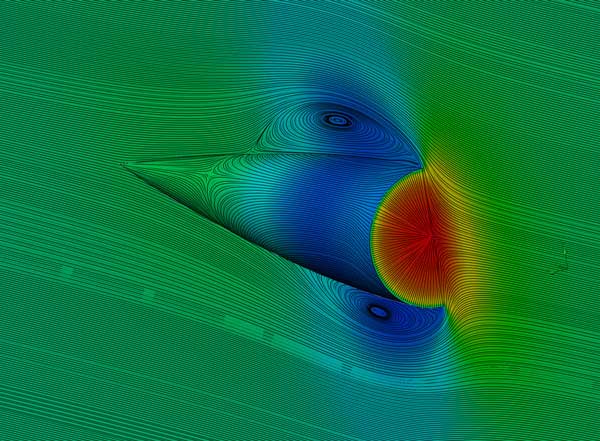

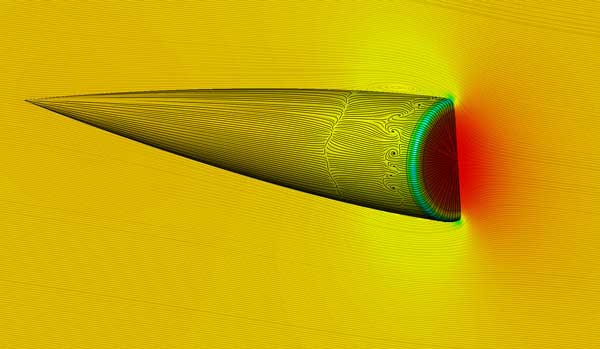

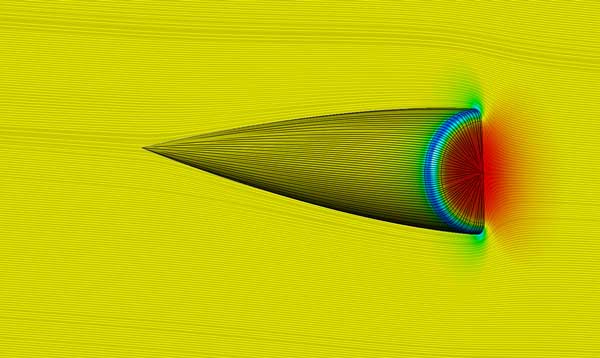

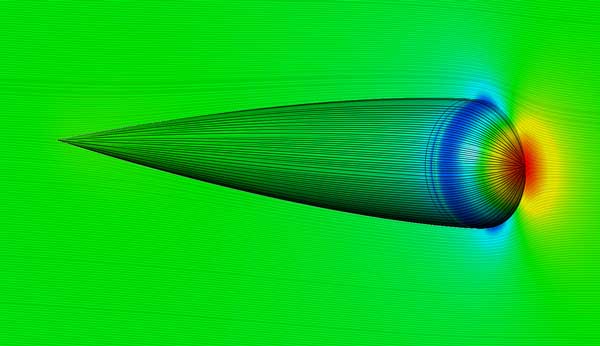

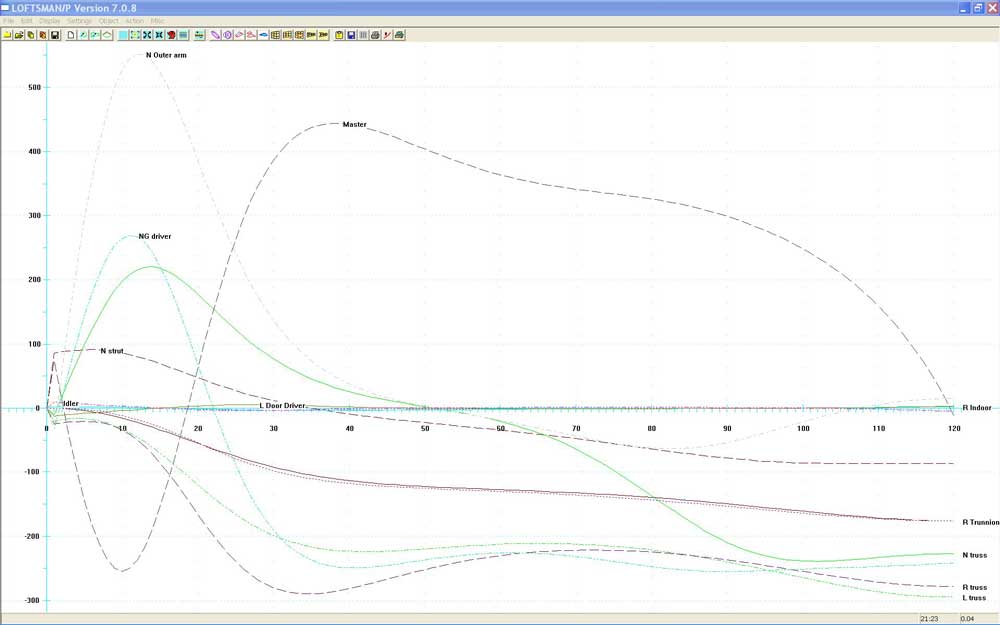

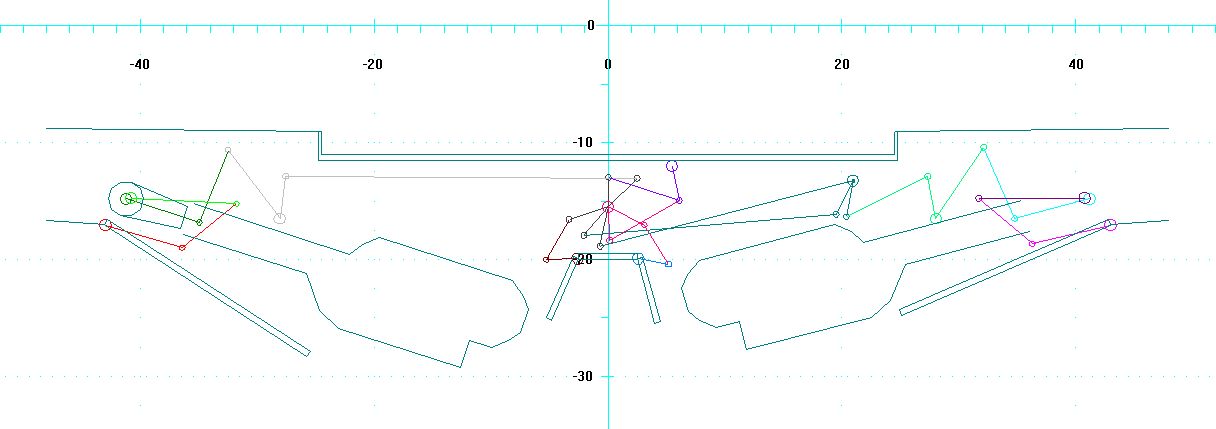

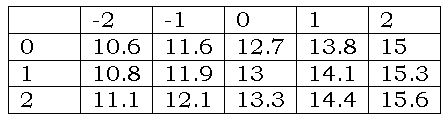

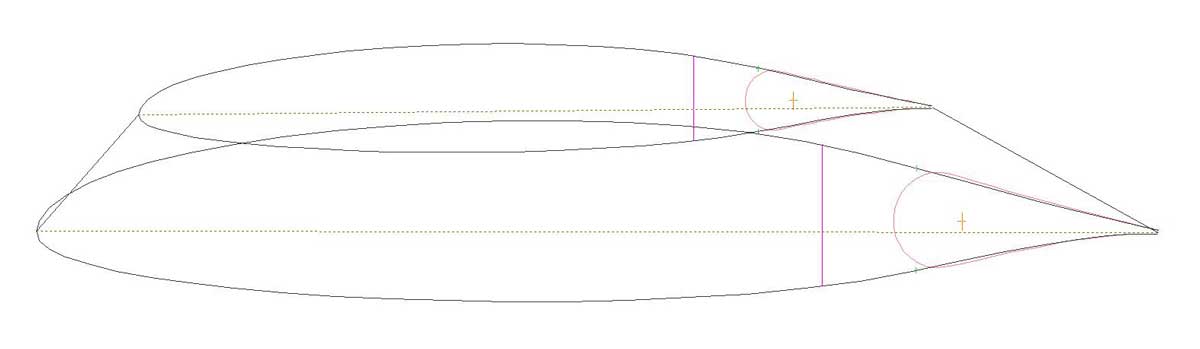

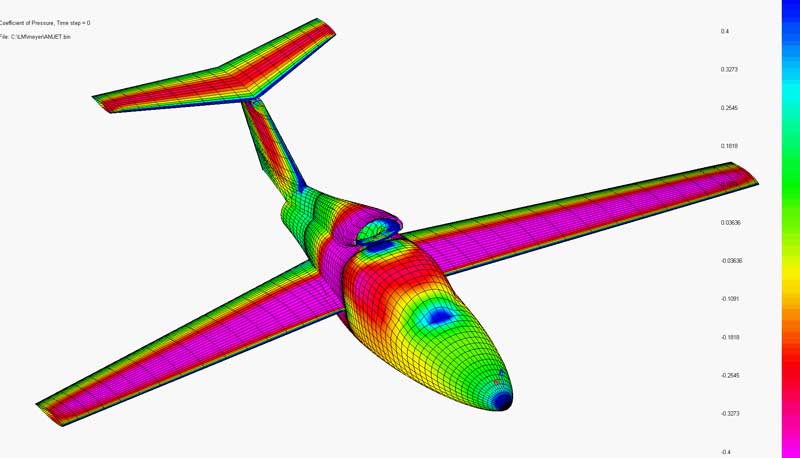

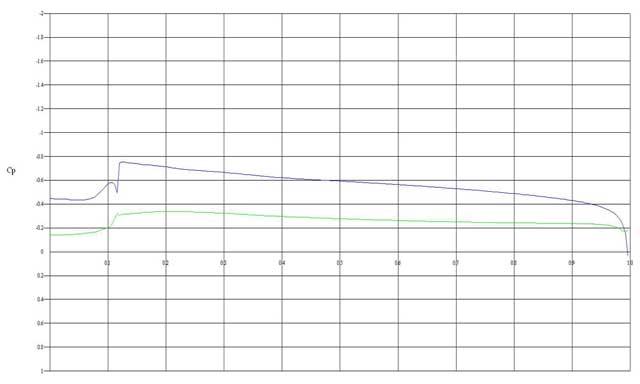

I asked, rhetorically, in the current issue of Flying, whether, if you sliced an airfoil-shaped body of revolution transversely at its thickest point, the bullet-shaped forebody or the blunt-faced afterbody would have the greater drag. My friend Hans Kandlbauer ran some simulations using Solid Works' RANS code, with the following results:

[February 17, 2021]

I did a cold compression check. All three cylinders on the right side of the engine were 80/80. the three on the left were 42, 64 and 71. This seemed odd, so I ran the engine for five minutes at 1,200 rpm, then shut down and repeated the check on #6, which was the lowest; it now showed 80/80. I don't understand compression checks; it seems as if you can get just about any result on any given day. The asymmetry is puzzling, however.[February 10, 2021]

A friend forwarded me a picture, taken by a friend of his, Elwood Schapansky, of the original Melmoth at Galena, Alaska, in July, 1976, a few days before Nancy and I flew over to Japan. I am surprised to see that 1) the airplane was so clean; and 2) the down jacket, which I still have, was once so puffy.

[January 8, 2021]

Oddly, it has now happened twice that the new micro-camera stopped working as soon as I took off. Today, however, I did get a gratifying speed point at 14,000 ft DA, 181 ktas at 9.2 gph, 63% power, which is slightly better than the computer simulation predicts.[December 19, 2020]

Last week was notable for ridiculousness. I re-did the calibration of the MS-28034 induction air temperature probe, and checked a spare as well (I have three -- the third is the oil temp probe). Both returned horrible calibration curves, with a true 100 deg C reading as 125, and 40 reading as 55. Since it is unlikely that two probes are identically faulty (and the oil temp, which I did not test, also indicates unexpectedly high), it seems probable that, as a friend suggested a few weeks ago, the problem is the three-gauge panel display, which is probably coeval with the B-47. If this is the case, then all my worries about oil temperature have been unecessary, since it has actually been in a reasonable range all along.[November 30, 2020]

Before Thanksgiving I moved the IAT probe, which is about 1/4 inch thick and a couple of inches long, from its position at the entry to the throttle body to one in the middle of the intercooler outlet tank. I did this in the hope that the asymmetry it created in the throttle body flow, which it entered from one side, might be responsible for the odd difference between EGTs between the right and left cylinder banks. The change turned out to have no appreciable effect. CHTs have always been very inconsistent front-to-back, but they do not show the same right-left imbalance as EGTs do. Yesterday at 12,500 ft d.a. I recorded these CHTs (Celsius) with partially open cowl flaps, ordered front-to-back:[November 14, 2020]

I added a heat shield to the portion of the duct leading air to the oil cooler. The result -- with the not negligible help of cooler weather -- was that the oil temps are now in the green. The temperature of air entering the cooler is now about 4 deg. F above ambient, so there is still some heating taking place on the way from the cowl intake, but it's slight. The temperature rise in the air passing through the oil cooler is around 75-80 degrees F. It was apparent that the vernatherm was working as intended, since there was no temperature rise in the air passing through the cooler until the oil temperature hit 160 F.

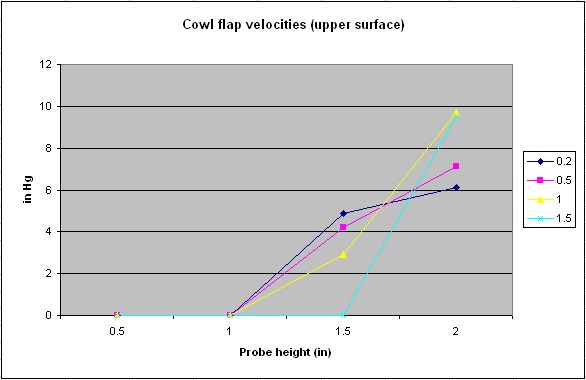

The oil temperature turns out to be quite sensitive to the position of the cowl flaps, which regulate the pressure drop across the cooler and the amount of air passing through it. This was the reason I originally provided the oil cooler with its own exhaust duct, separate from the cylinder cooling air. With cowl flaps open, oil temp was 185, fully closed 215.

I finally got a speed point -- 178 ktas at 9.6 gph at 12,500 ft -- that more or less matched predictions for an equivalent flat plate area of 2.35 sq. ft, so the intercooler and the pitot-style scoop on the side of the cowling have not added a huge amount of drag. They've added some, however. Maybe I should have a way to shut off the intercooler when I don't need it.

[November 2, 2020]

The duct is now installed.

[October 21, 2020]

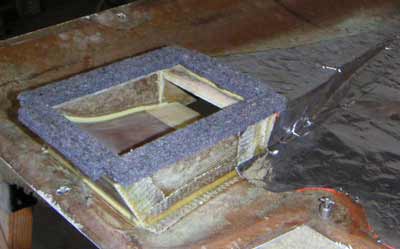

I see that it was just shy of three years ago that I contemplated providing a direct duct from the cowling air inlet to the oil cooler, to avoid an admixture of exhaust-warmed air. I have now almost finished the mold for this duct:

[October 13, 2020]

The oil and air temperature probes, which share the same indicator via a toggle switch, both read high on the ground (on a 38 deg C day. they read 50 C) but say 100 C when immersed in a can of boiling water; so they're okay. I decided finally to provide a separate supply of cold air to the oil cooler, and I am making tooling for that duct now. Now that the oil cooler will no longer be sharing an outlet with the intercooler, I can probably replace the hood over the opening with shark gills.[September 24, 2020]

No peace unto the wicked. I took out the nice oil cooling air outlet plenum and duct that I was so pleased with, closed up the holes it left, and moved the pressure probe line to the top of the (now intercooler only) outlet pan. The OAT was slightly higher than yesterday's: 94 F on the ground and 71 at 8,500 feet, or 42 degrees F above standard. Despite the change in the oil cooler arrangements, during the climb the oil temp went up to 240 F, same as before, and settled back to 230 in cruise.[September 23, 2020]

I collected a few pressure points from the plenum immediately above the oil cooler. To my surprise, the pressures there were quite high, even though the outside world is 12 inches away through a 10 sq. in. duct. Two representative values were 3.8 in. H2O at 120 kias and 5.1 at 140 kias. These correspond to delta-p's of 3.5 and 5.4 inches respectively. What is surprising about this is that the delta-p's across the engine are 6.5 at 120 and 7.9 at 140. In other words, I would get better delta-p across the oil cooler if I closed the external duct and simply let the oil cooling air spill into the upper plenum. This was the original arrangement, before I started messing with it about 10 years ago. I now intend to try reverting to it.[September 22, 2020]

I finally managed to get some video of the scoop tufts, but now I can't figure out how to download the video from my iPhone. However, I did some screen grabs, of which this is one:

[September 12, 2020]

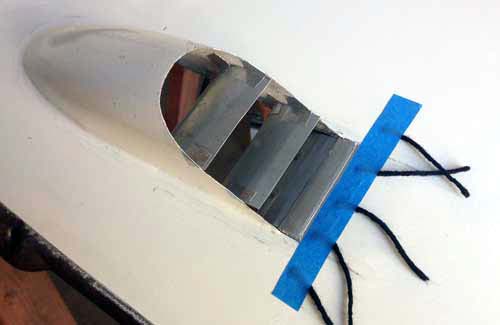

I tufted the scoop and then made two attempts to record video of the tufts in flight. Neither was successful. I belatedly realized that the camera rig I was using had no on-off switch, and was activated simply by connecting the battery to the camera. The charging port is on the camera, however, and so to charge the battery one must connect it to the camera. I had not done so, and when I turned it on before flying the camera would work for just long enough to persuade me that it was okay, but, once I was airborne, quit. I can see some of the tufts from the cockpit, and they were lying down nicely. Tufts are typically made of a loosely woven yarn, and one telltale sign of flow separation is tufts that are unravelled after flight. Tufts in smooth flow are undamaged. The only frayed tuft I had was one right in front of the center of the boundary layer channel; I suppose it may have been whipping back and forth across the stagnation zone.

In the course of the last three flights I noted unusually high oil temperatures. The ambient temps have been around 40 degree F above standard -- that is, in the high 90s -- but even so the oil temp is higher than expected. I checked the pressure in the lower plenum and got the impression that it's down a bit, perhaps because of leakage into the collector pan from which the intercooler and oil cooler air are vented. The pan is stationary -- it does not move with the engine -- and so I am removing its flexible perimeter seals and replacing them with a rigid barrier that will press into a rubber sealing strip on the inside surface of the cowling. There could be other reasons for the increased oil temperature, but since all are potentially more dire or difficult to deal with than this one, I might as well start with this.

Last Tuesday I climbed through smoke to 5,000 feet, hoping to get on top, but with restricted forward visibility -- impossible to tell whether it was three miles or half a mile -- and with the ground disappearing below me, I turned back to the airport. Yesterday and today the smoke has been dense, down to the ground, its campfire smell pervasive, the sun a faint orange disk or entirely invisible, all around an infernal and shadowless scene.

September 2, 2020]

[August 7, 2020]

The outer form of the scoop is now complete; only the afterbody behind the cowling parting line remains to be laminated, and then the whole thing needs to be smoothed and finished. The ivory paint with which I originally painted the plane 17 years ago, and of which I still have a serviceable can, now seems to cure with a faint purplish hue, so the repainted areas around the new inlet and outlet will be rather conspicuous; but no one has ever accused me of being overly fastidious about paint. Call it Murano.[July 30, 2020]

I finished the inner liner of the new airscoop today. (When I flew the other day, the front 4.5-inch duct and the boundary layer channel were not yet installed.) This will now be covered with a layer of foam, which will be sanded to a streamlined shape and glassed over. The inlet is 7 inches wide and 1.25 inches deep, and the boundary-layer channel is 3/8 inch deep. The afterbody will extend a little past the firewall along the side of the cabin and will incorporate a small flush scoop for the pilot's ventilator.

[July 24, 2020]

I flew today with the new air inlets partly installed. At present only the inner surfaces are in place; the outer fairing is yet to come. I was curious to see what speed penalty the sharp-edged, lipless excrescence would exact. At 10,500 ft, where the density altitude was 12,500, 9 gph gave an indicated airspeed of 143 for a true of 172. This is about three knots shy of what the computer model predicts. On the other hand, at 7.8 gph it was 138 kias (166 ktas) which coincides exactly with the model. So I suppose things won't be noticeably worse once I have the smooth fairing built.

[July 21, 2020]

I've been spending a couple of hours a weekday on the seemingly endless task of replacing the air inlets for the engine (NACA flush, very pretty) and intercooler (crude metal kludge) with a single pitot-style scoop. I am very sorry to lose the NACA inlet, the look of which I have always liked, but regret, as both Chief Seattle and Marlon Brando have said, is useless. I intend to incorporate into the afterbody of the scoop a smaller NACA inlet, a sort of consolation prize, to provide air directly to the pilot's ventilator. In the present arrangement, a single inlet on the right side supplies both pilot and front-seat passenger, and it is not too satisfactory for the pilot on hot days if the passenger-side vent is open. The two back seats share a single ventilator, but it produces a surprisingly powerful blast of air, as Russ Hardwick and I discovered to our sorrow when flying at a frigid 15,500 feet a few years ago. I resolved then to provide the pilot with the ability to shut off that ventilator, but have not yet done so.[May 27, 2020]

I found a nice picture online of M2 leaving Oshkosh in 2011. Takeoff flaps have not yet been retracted. This reminded me that there are still some bits that need paint. I wrote to the copyright holder asking for permission to post the picture on this site. I have not yet heard back -- it's been a couple of weeks -- but if he refuses I'll take it down. So study it carefully now.

[May 2, 2020]

To convert the geyser emerging from the top of the cowling into a more-or-less aft-facing plume, I removed the hood from the now-disused oil cooler outlet with an oscillating saw -- marvellous tool! -- cut it in half lengthwise, made it an inch wider, and tacked it over the new outlet with some fancy turning vanes added. I am now laminating this into place, and in the process am revisiting my long-neglected epoxy-metering equipment. My ratio pump is too gummed up to use without a thorough cleaning, but I find that a simple balance beam is almost as fast. In the past I used this method, when I used it, quite stupidly, piling up certain number of washers, moving them right or left to balance, and then increasing their number as needed to achieve the desired ratio when the second part was added. This time around it finally dawned on me to make a mark 10 inches from the balance point, and other marks at 12 inches and 14.4 inches, representing respectively the mix ratios for West System and EZ-Poxy. You put your empty mixing cup into the ragged-looking cup at the right-hand end and balance it with the big nut. You then pour resin into the mixing cup, balance it with washers at the 10-inch index -- you can precisely match the washers with a few extra drops of resin, if need be -- and then move the stack of washers to the appropriate index and add hardener to balance. I can't believe how long it took me to figure this out. Not so smart after all.

[April 17, 2020]

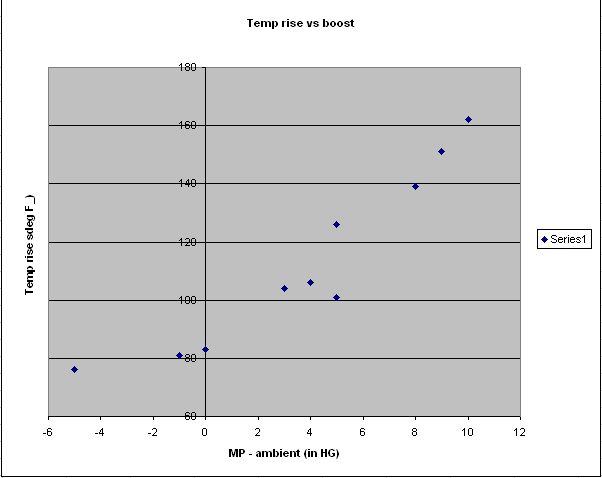

Initial test flights produced mixed results. Induction air temperature dropped by 30 deg C, from 65 to 35, with an OAT of 19 C. I'm not sure how good that is, but anyway it's going in the right direction. On the other hand, the oil temperature, which I optimistically expected to be lower than with the previous arrangement, initially settled at the top of the green, but then started creeping upward. Suspecting that this might be related to the fact that air from the oil cooler and air from the intercooler approach the outlet from opposite directions, I landed, taped over the intercooler air inlet and took off again. The oil temperature got even higher, which made no sense at all. On landing and removing the cowling side panel, I found that the neoprene gland at the bottom of the oil cooler duct had partially prolapsed, probably because of the large pressure difference across it. I'm not sure how that would affect oil temperature, but at any rate it's something that needs to be fixed. At the moment it's held in place by friction; I'll try a hose clamp. The tufts that I had affixed around the outlet on top of the cowling resembled the scene when a car collides with a fire hydrant; I began work on a hood.

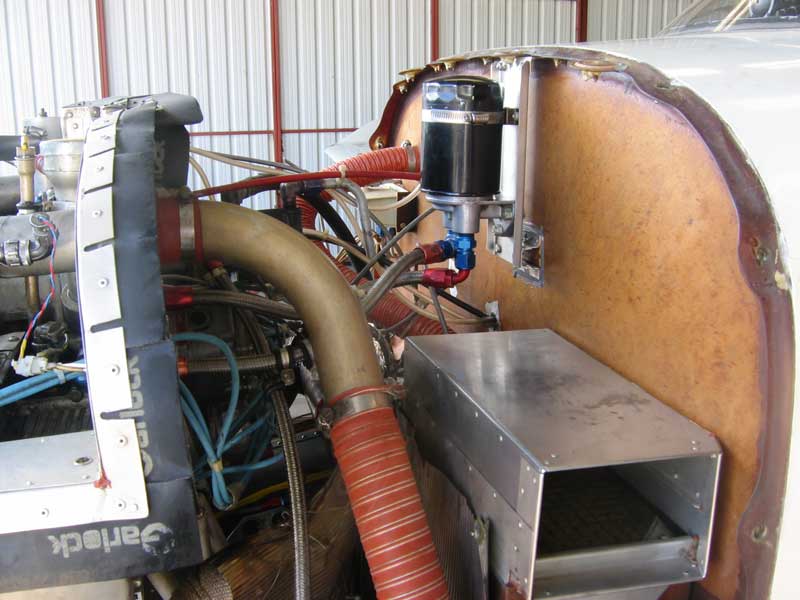

Here at last is the finished ducting for the intercooler and the oil cooler. Spent oil cooling air now goes into a box that protrudes through the rear baffle, and thence through a 3.5-inch duct into a plenum shared with the intercooler. The plenum vents through the top of the cowling; I am bandaging that wound now, and I hope to be able to test-fly the system by the end of this week. If all goes well, I will then turn my attention to the airscoop on the side of the cowling. It will replace the odd pairing of a crude temporary metal scoop and a slick NACA flush inlet (see below) and will provide air to both intercooler and engine. I shall draw my inspiration from the scoops on top of the cowlings of the DC-7 in which I took my first plane ride at the age of 10.

[March 25, 2020]

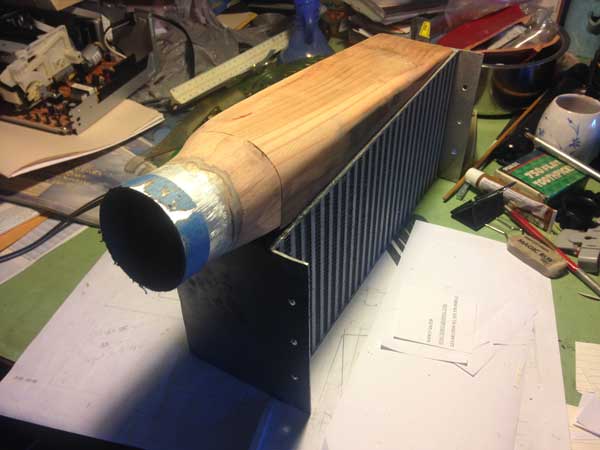

Today I added the flexible baffles to the air outlet box; tomorrow I'll cut the dreaded hole in the top of the cowling. Yesterday I flew with a temporary airscoop feeding cooling air to the intercooler. The air, having passed through the intercooler, merely flowed into the cowling. Nevertheless, the induction air temperature was lower than usual. The scoop is homely, but at least it has its own boundary-layer channel:

Progress on the intercooler project, which began two years ago, has sped up markedly. One of the reasons for this -- not, I'm sure, a very sensible one -- is that I would like to get the system finished, along with the oil cooler ducting to the new hot-air cloaca on top of the cowling, so that the plane is at least complete, if not clean, in case I contract COVID-19 and die.

[March 13, 2020]

The intercooler is now equipped with its inlet and outlet ducts. The inlet is the upper of the two rectangular openings below the intercooler; the lower one is the engine induction air filter box. The outlet is the tray on top, which is eventually intended to receive both intercooler and oil cooler air and send them out a louvered vent on top of the cowling. The current protruding outlet for the oil cooler will disappear. I've partially built the duct in the side panel of the cowling that will bring cooling air to the intercooler, but I haven't cut the hole in the cowl side yet -- I hate cutting into these pristine surfaces. Also, I have been busy lately with an apparatus from which the ashes of an old friend will soon be scattered into the Pacific Ocean.

[January 22, 2020]

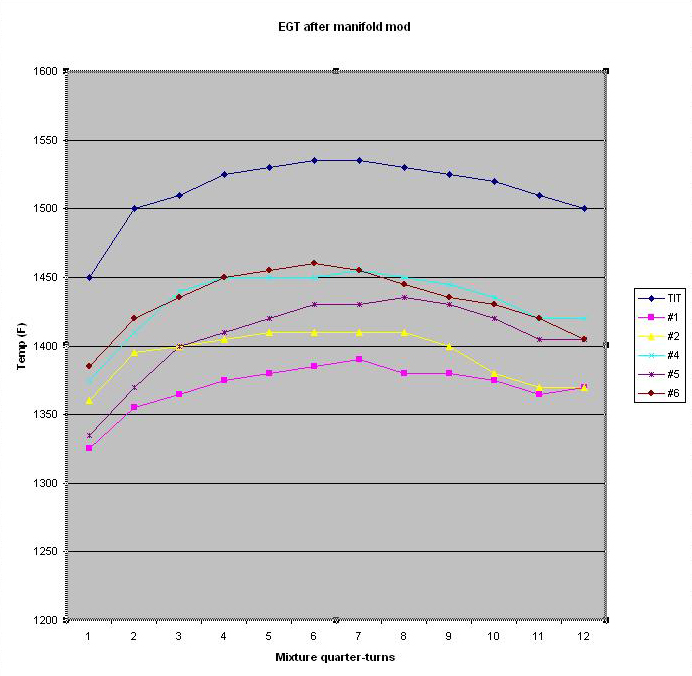

The Christmas season is hopeless for getting any work done on the airplane, as I have regularly complained before. Early January does not seem much better. I did collect some rough data on EGTs, and found that while messing with the induction did not noticeably affect the synchronization of peak EGTs, it did somehow or other cause the right-side cylinders to collectively run at higher EGTs than the left-side ones. I asked George Braly at GAMI about this, and after offering various comments and suggestions he added a quotation from Richard Feynman about the easiest person to fool being yourself. I have often fooled myself in the past, and am prepared to believe that I am doing so again now. After I have the intercooler plumbing completed I will do a careful survey of EGTs and possibly add a flow straightener or an adjustable vane just ahead of the throttle inlet in order to equalize the flow to the two intake-manifold logs.

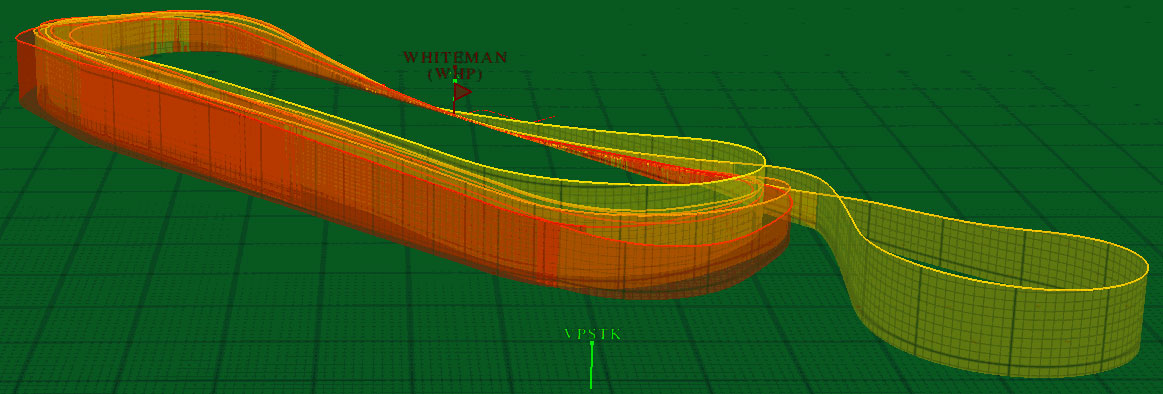

In my previous entry I bashfully admitted to having made a really beautiful landing on a particular flight. Well, I am about to do so again. My landing yesterday was perfect. I feel free to say this because while Melmoth 2 is not a difficult airplane to land well, I seldom manage to get all aspects of the landing to work out perfectly, and so I either land at a slightly higher airspeed than ideal, or with more of a tap (or bang), or I don't put the nosewheel down as gently as I would like to because I run out of tail authority (being alone, and therefore noseheavy). There are some tall things sticking up just across the street from the approach end of Runway 12 at Whiteman, and, although you'd have to be awfully low to actually hit one, I tend to come in a bit high and chop the power just short of the end of the runway, with the displaced threshold still several hundred feet ahead. The glide steepens noticeably before I begin to flare. Ideally, the nose is still coming up as the tires get within a few inches of the surface. I like to get the nose really high, stall warning blaring, and on touchdown -- nearly imperceptible, of course -- lower it with sufficient control to arrest the wheel just before it touches and place it gently on the runway. At that point the speed is under 40 knots and I easily make the midfield turnoff. There is nothing extraordinary about any of this; it's really just a matter of chance to get all components right. But, as any pilot knows, it's a good feeling when you do.

[December 14, 2019]

The intercooler passed its first functional test, viz. it did not fall out of the airplane during its first two flights. After suitable delays for meleagricidal late-November activities, I got the outlet tank re-contoured, boldly sawed a 90-degree bend out of the existing duct, and put it all back together. At first it appeared that replacing the short elbow with a long one had made no difference, since on runup I found that the right-side EGTs were still much higher than the left-side ones. It then dawned on me that I had never established a baseline; I had merely assumed that since EGTs are pretty even in cruise, they must be in runup as well. For that matter, I never look at the EGT or CHT during takeoff, and so my impression, during the first test a couple of weeks ago, that CHTs were rising ominously may have been spurious.

I removed the intercooler again -- I've gotten pretty good at it -- re-installed the old duct and did a run-up, which revealed exactly the same behavior. It may be that even the short elbow was not having the enormously detrimental effect on mixture distribution that I thought, but the 6-inch radius aluminum duct looks a lot better. I put the intercooler back in, flew to Santa Paula, bought some relatively cheap gas ($4.35/gal vs $5.59 at Whiteman), and flew back to Whiteman, where I made, I must say (because I can't always), a really beautiful landing.

At present the intercooler is just a rest stop along the way from turbocharger to throttle body; I have not yet made any provision for cooling air to flow through it.

[November 23, 2019]

It turned out that the outlet "tank" could be shortened fairly easily to accommodate the same aluminum elbow of 6" radius as is now part of the pipe that runs from the turbocharger to the throttle body. I just need to do a little sculpting with filler -- a mixture of epoxy with plastic microspheres for lightening -- to smooth the internal contours of the tank. The intercooler will then be rigidly supported at its inboard end -- no more spring -- and sufficient (I hope) flexibility will be supplied by joints at both ends of the aluminum elbow. There is no guarantee that the flow distribution in the intake manifold will be entirely unaffected by a heat exchanger replacing a length of straight pipe; but I think the effect, if any, ought to be much less than that of the villainous blue elbow of yore.

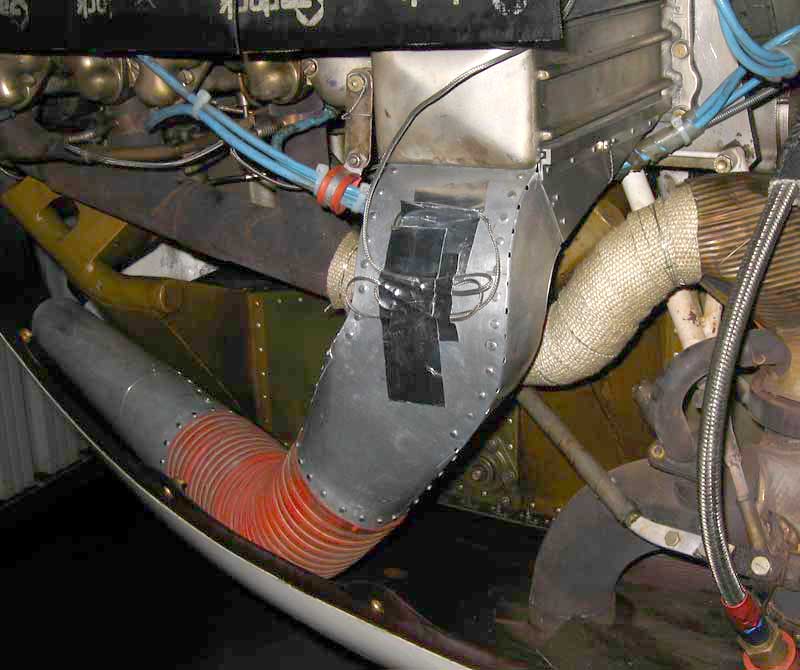

Going back through this chronicle, I see that I never supplied a picture of the present plumbing connecting the turbo to the intake manifold. This is it:

The long duct consists of a bunch of pieces of .035 wall aluminum tubing spliced with bands of fiberglass cloth and epoxy. I don't know where I got the tubing, but I wish I had more of it. I will have to saw the 90-degree bend out of the top end. I would prefer to keep the old duct intact in case the new arrangement doesn't work; but there's no choice.

[November 15, 2019]

Physics 1, Hope 0.

At least I was not so naive as to be unaware that that short elbow might cause trouble. I just hoped it wouldn't, and told myself you never know with fluid flow, which is true, generally. However, by the time I was halfway to the runway for the first test flight, it was obvious that the right side of the engine was running much leaner than the left. I began a takeoff, but aborted it when after a few seconds the CHT I was monitoring (#3) hit 200 deg C (392 F). Normally, the engine does not get to that temperature until I am well established in the climb. I returned to the hangar, removed the intercooler, put the old duct back into place, and went flying.

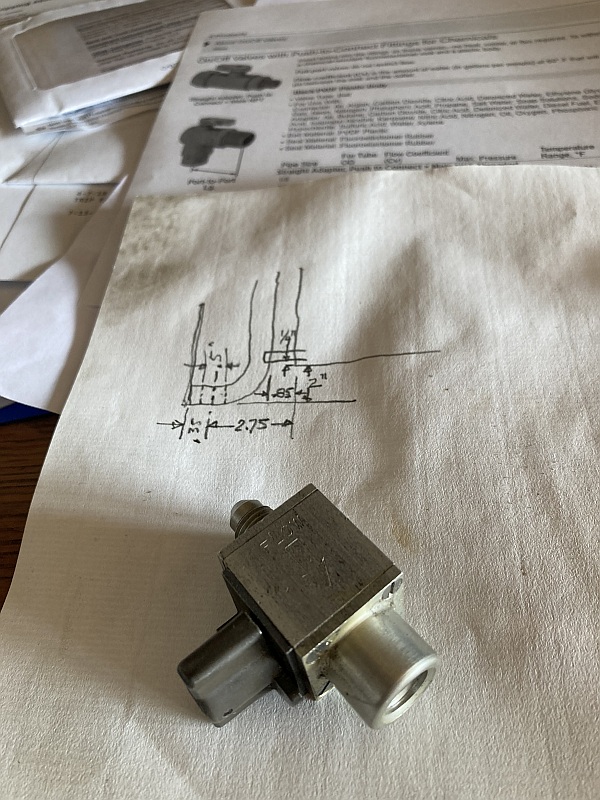

I need to revise the shape of the duct on the outlet side of the intercooler to allow a bend with a radius of six or seven inches between it and the throttle body. That is the radius of the bend in the current pipe, and it works fine. But this puts me back in search of a 2.25-inch I.D. hose sufficiently strong to handle 1 atm. of overpressure at, say, 250 deg. F, and sufficiently flexible to 1) make a 6-inch radius bend without wrinkling on the inside and 2) allow some freedom of movement between the engine and the intercooler.

[November 7, 2019]

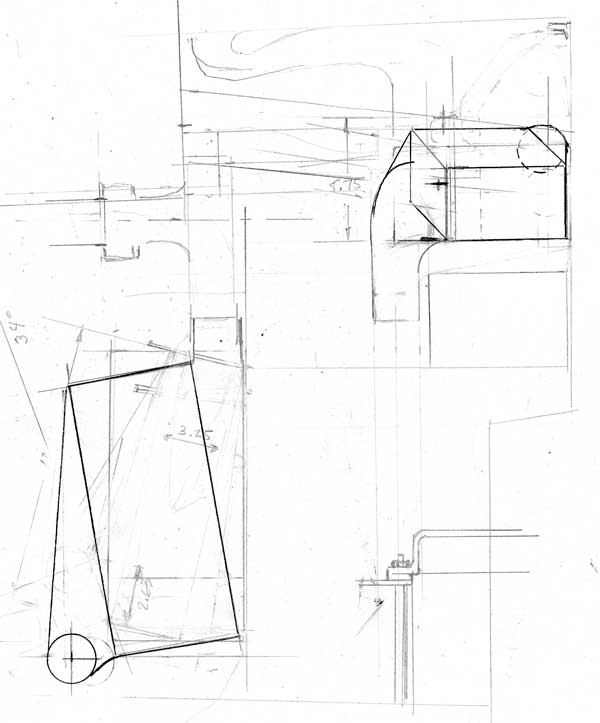

After much hesitation about how and where to mount the intercooler, I settled upon the above arrangement. The difficulty is that the intercooler is secured to the airframe, but connected to the engine, and the distance from the throttle body to the intercooler outlet is too short to allow for the full range of motion of the engine. The solution I am trying -- which may be no solution at all -- is to mount the outboard end of the intercooler to the firewall with a flexible shear clip made of .016 stainless steel sheet. A diagonal strap removes bending loads on the mounting lug, which is bonded directly to the honeycomb firewall and should, in principle, experience only shearing forces parallel to the firewall surface and a compressive force against the firewall. At the inboard end, a coil spring provides several pounds of lift, so that the flexible duct is not carrying the weight of that end of the intercooler. The inboard end of the intercooler does have some freedom of movement, however, to allow for the engine jumping around during startup and shut down. I'm not happy about the very tight elbow, but it was all I had room for even though I used the shorter of my two intercoolers. I started the engine today just to confirm that the assembly did not immediately fall apart. The next step will be to attach the fiberglass ducts to the intercooler and re-run the inflight EGT survey to see whether the elbow is affecting the mixture distribution. If the system passes that test and doesn't disintegrate in a few hours of flying, I will add the ducts for the cooling air.

[August 26, 2019]

The inlet and outlet ducts are finally, albeit temporarily, attached to the intercooler:

In the picture the intercooler is upside-down; the pipe on the left connects to the turbocharger, which is below it, and the one on the right goes to the throttle body. It actually fits into the airplane like this:

You can just see the turbo outlet as a dim red crescent at the bottom of the picture.

My present plan is to provide a pitot-type (i.e. non-flush) inlet for the cooling air, because flush NACA inlets are not effective unless there is a negative pressure gradient downstream. The cooling air will vent upward out of the top of the cowling. I plan to remove the present hooded outlet for oil cooler air and vent that air to the same outlet as the intercooler's.

[July 30 , 2019]

A week ago I finally took the intercooler to a welder to add the flanges to which the charge air ducts will be attached. I got it back yesterday. Since I changed my mind about which to use of the three intercoolers I have collected over the years, I had to saw about four inches off the outlet duct, which I had already made, and I will have to modify the inlet duct mould similarly before making that part. After lengthy mental calisthenics visualizing various ways in which the intercooler could be installed, I finally concluded, by dint of propping it up in place, that my first plan -- that of March 23, 2018-- was the best, or at any rate no worse than any other. Getting fast-moving induction air around the corner from the intercooler outlet to the throttle body inlet requires a 2 1/4" I.D. flexible elbow with a 7-inch radius of curvature. I found something at McMaster-Carr that should work. I also found ready-made aluminum tubing segments with beaded ends, which I will bond into the laminated ducts. So the design and materials of the induction air plumbing are more or less settled. As for the cooling air, I am leaning toward a pitot-style external scoop for both the intercooling and induction air, located where the NACA flush scoop is now, and some sort of louvered outlet on the top of the cowl, directly above the intercooler. I am also thinking of ducting the oil cooling air to that same outlet and dispensing with the hooded vent I am using now. The drag penalty of an external scoop and an additional heat exchanger is hard to foresee; if it represents an increment in F, the "equivalent flat plate area", equal to the frontal area of the inlets, it will be barely acceptable in exchange for cooler induction air and greater detonation margins.

[June 1 , 2019]

Nancy and I got back from a week-and-a-half trip to the east -- college reunion -- this morning at 2:00 a.m. I was planning to fly up to Paso Robles for Chuck Wentworth's annual Antique Aero BBQ, but LA has been socked in all day and I'm not remotely current, so I stayed home. This has given me time to think about all the things I need to do, mostly tedious. Having relieved the AT-50's 12-volt power supply of its duties, I now have to find another job for it. M2 has two of those Narco 24-to-12 converters, actually; I think the other powers a 12-volt outlet. Can I simply hook them together, in parallel, or would that engender inner conflicts? (Being ignorant of electronics, I have to launch queries like this into the ether, like Noah's dove.) Poking about back there also reminded me that I have never connected my pitot and AoA tab heat -- not that I will ever use those things in my ever-less-ambitious flying. Furthermore, installing the new transponder somehow caused my glideslope receiver to quit working; a loosened connection somewhere, no doubt. The intercooler, meanwhile -- like Hope, it is forever deferred, but never extinguished -- awaits the creation of the second "tank" and the addition to the heat exchanger of a couple of aluminum flanges to which the tanks will be secured.

While we were in the East, by the way, an unusual event occurred. Someone streamed Jaws, and, of the four people present, three -- Nancy, our daughter Lily and I -- had never seen it. A genetic thing, I guess.

[May 5, 2019]

A couple of days ago I did another evaluation flight and requested a PAPR report from the FAA. It came back with exactly the same fault as before I changed transponders, and not only the same fault, but almost exactly the same percentage of non-received Mode 3A squawks. This time, however, I heeded the advice on the FAA site to contact them before heading off to the radio shop. I got a very prompt and nice reply saying that the dropped squawks were due to being at low altitude or behind mountains or otherwise out of coverage, and my equipment appeared to be working fine. So I guess I can start thinking about something else for a change.

[April 24 , 2019]

Success! Today everything worked. Or let's say, at least, that I was unaware of the things that were not working.

[April 23 , 2019]

Installing the new transponder was more of a job than I anticipated, but after a day of fumbling around I got it and the wire harness installed. The Narco transponder used 12v power, and required a power converter; the Garmin is omnivorous, and so the connection between it and the bus had to be rewired. The power converter remains in service for a few other 12v things. Making the new connector for the Garmin turned out to be the simple part; I got a beautiful little crimping tool online for $30, and putting the right wire into the right hole was not much of a challenge, except in one instance where, in the twilight of my years and workshop, I mistook a dark brown wire for a black one and as a result deprived the altitude encoder of its ground. When I first powered up the transponder yesterday it was not displaying altitude -- this was due to the missing ground -- but appeared otherwise correct. When I got into the air, although the "reply"indicator was blinking in a realistic way the tower was seeing no return. Today I fixed the missing ground and re-installed the fitting on the transponder end of the antenna cable. The transponder now displays altitude -- correctly, to boot -- but I ran out of time and will test fly it tomorrow.

[April 12 , 2019]

One of the two intercooler tanks is now done. Unfortunately, I took a second look at the heat exchanger core that I had decided not to use, and I began to think that I might be better off with it than with the one I had first chosen. It's shorter, and will give me a little more freedom in arranging the parts of the system and their associated ducts. That means that the tank I have made is too long; but it will not be difficult to shorten it, and also the mold for the other, if that is what I decide to do. In the meanwhile, after what seemed to me a torturously long delay, I finally got the Garmin 327 transponder, which is supposed to be the solution to the Tailbeacon-related issues, and have been making up the wire loom for it and installing its remarkably stout steel rack in place of the AT-50A's aluminum one. I hope to be flying again by the end of next week. The airplane has not been in the air now for more than a month.

[March 22 , 2019]

I finally got back to the intercooler project after 10 months of idleness. The first of two layups of the outlet "tank" appears to have been a success, to the extent that 1) the epoxy hardened and 2) the part came off the mold without my having to destroy either. The part consists of four plies of glass with carbon fiber facings on the inner and outer surfaces of its relatively flat back. It's laminated with a high temperature Hysol epoxy. A second portion will be laid up covering the underside of the round tube, and overlapping, but not bonded to, the first. The final operation will be to bond the two parts together around a short length of aluminum tubing, without the male mold inside. The parts for the inlet tank are broadly similar.

Paul Lamar, the rotary engine advocate, gave me a bunch of books, including the classic Kuchemann and Weber text on internal flow systems. It reminded me of what I already knew -- because I made the oil cooler outlet duct that way -- but evidently forgot while I was designing the intercooler outlet tank, namely that while the inlet (that is, the high-pressure side) can be wedge-shaped, the outlet should be more like a rectangular box with equal clearance across the whole face of the heat exchanger. The effect will be to make one end of the intercooler less effective than the other. The whole thing is probably bigger than it needs to be, however, so the design is non-optimal from the start.

In the meantime, my transponder has been at High Desert Avionics at Fox Field for almost two weeks, waiting for an adjustment which I hope will allow the system to pass the FAA test. It almost passed on the second try, and what it did not do well was something that, if I understand it correctly, was due to the transponder, not the Tailbeacon.

[February 18 , 2019]

A correspondent who spoke with the Tailbeacon people told me that they pronounce it "you-Avionics", which is the least logical of the possibilities, unless they are trying to appeal to the "me generation". Another correspondent expressed concern over the thing being hard-wired on at all times, since that exposed it to voltage transients on engine start. He suggested putting it on the avionics master switch. There was no avionics master switch -- the first Melmoth didn't have one either -- but I decided to capitulate and add one. This turned out to be easy to do, since all of the avionics breakers are in a single row on the breaker panel. I used the old master switch from Melmoth 1, which is a somewhat bulky thing that you have to pull outward to toggle, and I put it over on the right side of the panel, beside the breakers, on the theory that if switching the avionics on and off involves a somewhat unusual group of motions, I'm more likely to remember to do it.

[January 29 , 2019]

First of all, it turns out, when you look closely, that the name of the company that makes the Tailbeacon is not actually uAvionix but mu - Avionix, that is, Greek letter mu, meaning micro. So I don't know how to pronounce it. Is it you-avionics, mew-avionics, or micro-avionics? In any case, I tried an FAA acceptance flight, which basically involves flying around for half an hour and making a few 360-degree standard-rate turns. You then get online and ask an FAA computer somewhere for a report on the quality of your ADS-B out returns, and in a minute or two you get an email, which said, in my case, that the system did not meet the requirements.

The next step is to use a cellphone app to adjust the sensitivity until the beacon and the transponder get into sync. It requires having regular transponder interrogations, so I have to find an airport around here where I can be on the ground (the app works only on the ground) and the transponder is blinking. I changed some wiring around so that the tailbeacon and its integral tail nav light are always on when the master switch is on; only the wingtip lights are switched from the panel. While I've been fiddling with this, two unrelated things went wrong: the attitude indicator tumbled (and would not untumble on subsequent flights) and the Lowrance GPS went dark. I sent the AH out for overhaul; the problem with the Lowrance turned out to be a blown fuse. I don't know why it even has a fuse, since it's on a breaker; but anyway, I put in a new fuse and it's working again.

This is what the beacon looks like (the thing next to it is a halogen flasher that I use in lieu of a strobe):

![]()

[January 17 , 2019]

In December I finally sprang for an ADS-B out transmitter. I selected the uAvionix Tailbeacon for a number of reasons, not least its price of $1,600. Still, only a diamond ring would cost more and come in a smaller box. Its installation, which I did a few days ago, involves an absolute minimum of alteration to the airplane. It simply replaces the tail light. When it is installed on a TC'd airplane the nav lights have to be kept on at all times; I intend to separate the tail light power supply and ground from those for the wing lights and run only the tail light/beacon continuously. I don't know how the thing works, but I assume that it just listens for a squawk from my extremely legacy Narco AT-50 transponder, and when it detects one it tacks on a few extra syllables of its own to report my ID, position and altitude. I am hoping that my Stratus 1, iPad, and the Tailbeacon will keep me flying in the ATC system for a few more years. I heard some dire grumblings about this being the first step toward user fees, which general aviation has been opposing for the past half century or so. Maybe, maybe not. I remember when the transponder requirement was denounced as the final nail in the coffin of our liberties.

One question that people ask about the Tailbeacon is, if it's entirely self-contained and just screws onto the taillight mount, what's to stop somebody with a screwdriver walking off with it. Well, first of all it's associated with a particular airplane -- you program it through your smartphone -- and you need a secret password to change that. Furthermore, the two #4 screws that hold its mounting plate in place end up behind the antenna, so you can't get at them with a screwdriver. The gadget itself locks into the base with two tiny allen screws, and unless I am mistaken they are either metric or of a strange intermediate size, because only the wrench that came with the beacon was able to engage with them.

It might be easier to steal the propeller.

[January 10 , 2019]

Looking through some old files, I came upon a letter that Mike Melvill wrote in 2002, when he was helping me fly off the 25 hours to get Melmoth 2 licensed. In it he reported the results of some speed tests. I thought it would be interesting to compare these to present performance, so yesterday I went up to duplicate at least part of his tests. I quickly realized that this could not be a very meaningful exercise, because at the time he did the tests the airplane did not yet have static ports, relying instead on cabin pressure for a static reference. Cabin pressure is generally below ambient because of leakage around the windows into the low pressure around the canopy, and so his results would be on the high side. Furthermore, at that time the airplane did not yet have a fuel flow meter, and so a direct comparison with the way I determine power setting today was not possible. Mike had recorded both fuel pressure and EGT, but much had changed about the engine since then, and I was now unable to duplicate his conditions. I gave up the intended comparison for a lost cause, but I did record a series of speeds at a density altitude of 11,000 feet, 2,500 rpm, and manifold pressures from 18 to 28 in. Hg. Not surprisingly, these coincided well with my computer model, which at this point does a pretty good job of impersonating Melmoth 2. Eleven gallons an hour, or about 75% power, produced 190 knots true airspeed. This would go up to around 197 ktas at 18,000 feet at the same fuel flow. Too bad; an even 200 would be nicer. Maybe if I ever get around to making the tires narrower. From the point of view of comparing 2002's performance with today's, the outing was a bust, but it proved fiscally fortunate: I stopped for fuel at Santa Paula, where I bought 30 gallons at $3.99 a gallon. I later ran into my hangar neighbor Claude Morgan refueling his exquisite 210-hp Swift at the Whiteman gas pit, where he had just had to pay $5.49 a gallon for the same stuff. A week's worth of visits to the local espresso joint!

[January 3 , 2019]

It's been a month since I last flew, owing in part to the Christmas holidays and in part to the failure of the batteries to hold a charge. I decided that rather than coax a little extra life out of the batteries by keeping them on a "battery tender," a supposedly useful practice that did not work out well for me when I tried it seven years ago, I would just replace them. This led to visits to four AutoZone stores, which have netted me so far one battery out of the required two. The hunt continues today. I contemplated switching from wet batteries to the sealed kind, which are more expensive ($100 each vs $60) but preferable in several respects. I was deterred by the sealed ones' not having exactly the same terminal geometry as the wet ones. Since my plane has solid connections in the battery box, it accepts only one style of battery. I may have to change that; I got the impression from the selection of batteries on display that sealed ones are more prevalent than the other kind, perhaps because motorcycles get laid down from time to time. One of the AutoZone guys said, by the way, that three and a half years was a good life to get out of these batteries; they usually last two. Hence the name "Duralast."

In the department of ludicrous blunders, I installed a microswitch to produce a bleat when the flap reached the takeoff setting, ie lots of area-increasing aft travel but little deflection. I thought I had the microswitch in the right location, but on the second flap retraction the roller went to the wrong side of the rod end over which it was supposed to ride, pretzelizing itself.

[December 19, 2018]

My Duralast motorcycle batteries have stopped holding a charge, at least for more than a few days. They're three and a half years old, so I suppose, since they cost about half what a 28-volt aircraft battery costs, I should not grumble. My previous Yuasas lasted just three years.

[December 5, 2018]

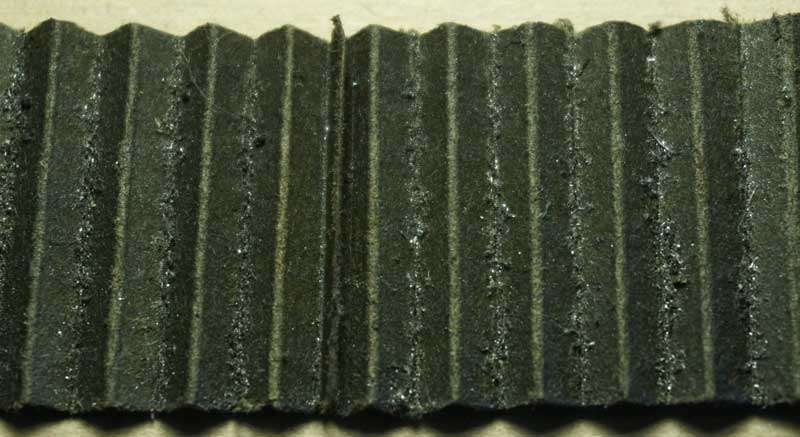

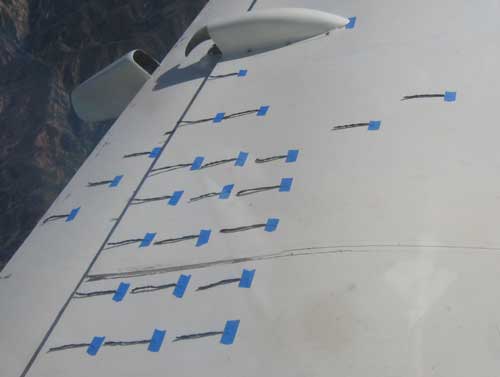

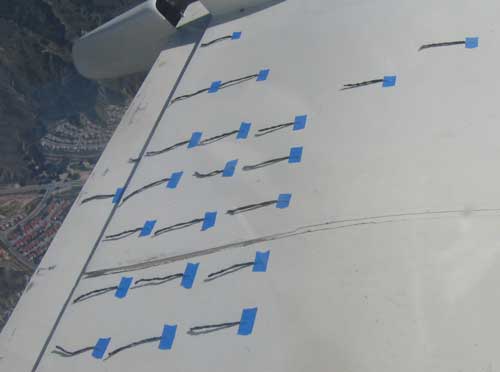

A couple of windstorms blew a lot of fine silty dust into the hangar, where it settled on the airplane. Today was showery, and I went flying in hope of getting some interesting streaks in the dust. I was lucky, in that there was enough rain to make streaks but not enough to wash the wings clean. After landing I took a number of pictures that reveal interesting details about the boundary layer flow. A few of them follow. The contrast has been exaggerated considerably to make the effects more visible; the airplane was not really covered with so much dirt that you could plant potatoes in it.

In the first picture, taken from the left wingtip looking toward the fuselage, the extent of laminar flow can be seen from the fact that the skin is clean from the leading edge back to around 40% of chord. This may not represent the true extent of laminar flow on the clean wing, however; the rain and dust themselves accelerate transition.

The next picture shows the right wingtip. The extent of laminar flow is much smaller, in part, at least, because leading edge sweep makes it more difficult to maintain. It's instructive that there is a pool of separated flow in the bend, where the pressure recoveries on the wing and the upturned tip form a mildly divergent channel.

The third picture shows another area of dead air, this time the upper surface of the aileron. The boundary layer evidently thickens significantly, or separates entirely, aft of the gap.

The next picture illustrates a curious phenomenon: spanwise flow near the trailing edge. The flow direction is inboard on the upper surface and outboard on the lower, and is related, I assume, to spillage at the tip and to formation of the tip vortex.

Finally, here is the flow around one of the flap track fairings. It's interesting that the flow does not hug the fairing, but seems to spread out away from it. There must be a pool of low-energy air close to the intersection. I don't know whether more of a fillet would improve the situation; I doubt it. In this picture, as in the first one, the transition from laminar to turbulent flow is visible.

[November 1, 2018]

It seems remarkable that this year had no October.